Author: Hanna Baan Hofman

“Black-and-white water tanks are ubiquitous on the roofs of Palestinian homes across West Bank cities and towns, to be filled when their water taps literally run dry for weeks at a time. … The Israeli authorities refuse to grant the necessary licenses to the Palestinian water authorities to operate freely in the areas classified as C and under complete Israeli security and administrative control, whether it is for drilling additional wells or installing booster pumps.” – Al Jazeera, 2021

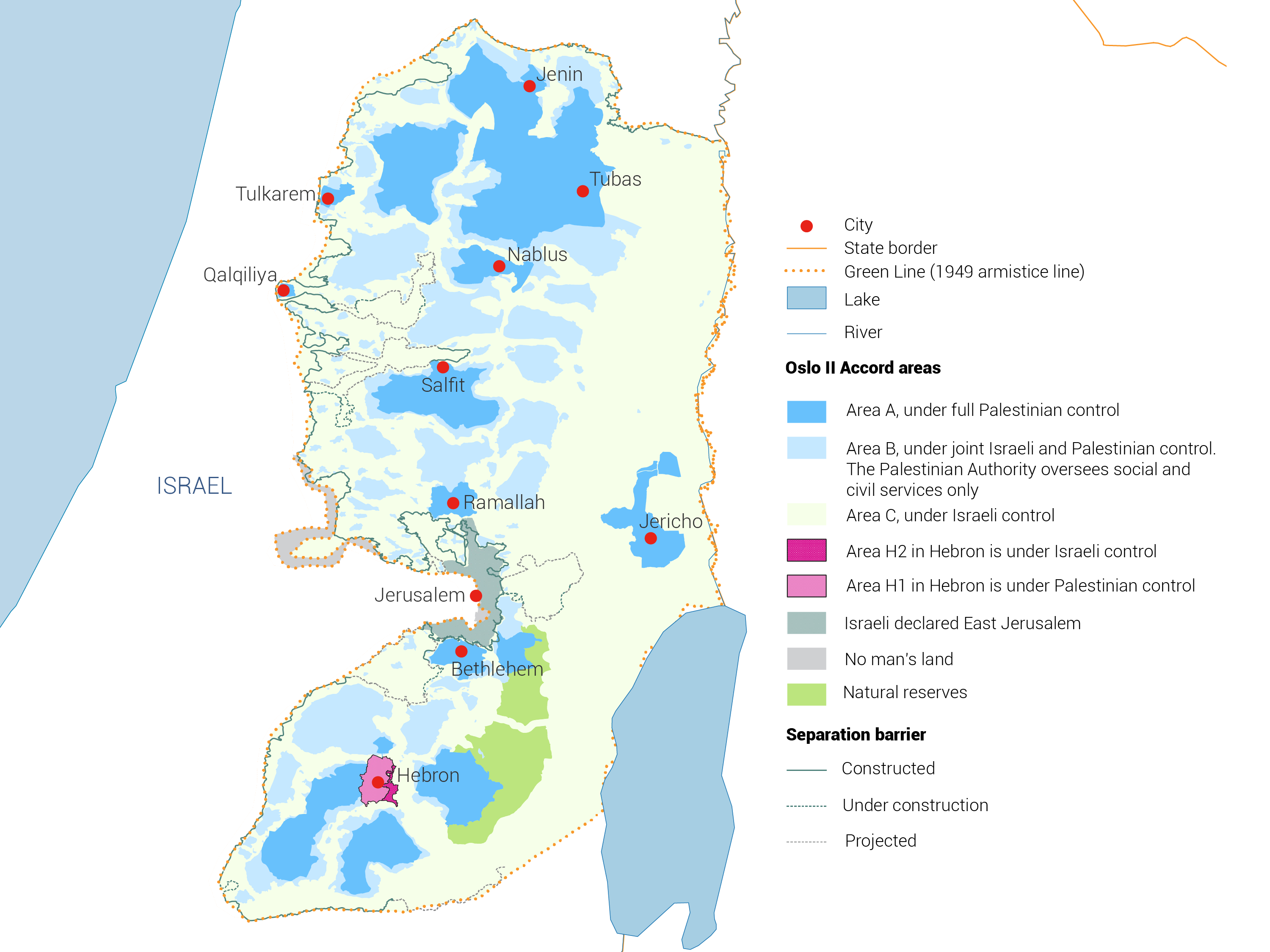

Palestinians in the West Bank suffer severe water shortages. However, data indicates that this is not a climatic or hydrological problem. Renewable groundwater resources are estimated to be 680 million cubic metres (MCM) annually. Divided over a population of 3.1 million, this means that in theory there are 600 litres of water available per person per day. In reality, Palestinians’ access to these resources is restricted, resulting in a net supply of just 60 litres per person per day in urban areas. In rural areas and those classified as Area C (Map 1), it is even less. In 150 communities in the West Bank, water consumption falls below 30 litres per person per day. This is significantly below the minimum of 100 litres per day as recommended by the World Health Organization.

In the illegal Israeli settlements in the West Bank, water storage tanks on rooftops are virtually absent. For Israeli settlers, water is available 24/7. Settlers make up 451,700 – or just under a sixth – of the West Bank’s inhabitants and consume on average 400 litres of water per person per day. In short, the water stress Palestinians face in the West Bank is not caused by a lack of water but by unfair distribution.

The role of territorial fragmentation in unfair water distribution

There are several reasons for the unfair and unjust water distribution. Israel claims there is a water shortage and blames the Palestinian Authority (PA) for mismanaging the water resources. The United Nations (UN) and several human rights organizations refute this, stating that it is primarily territorial fragmentation and unequal power relations that obstruct effective water management. The Palestinians first lost sovereignty over their water resources after the 1967 war. In 1982, all the water infrastructure controlled by the Israeli army was privatized and handed to the Israeli water company Mekorot. In 1995, as part of the Oslo II Accord, the West Bank was divided into three administrative areas known as A, B and C. Israel was given full control of Area C, which comprises more than 60% of the West Bank. As water access is bound to land, this gave the Israelis extensive control over the water sector in the West Bank. This is visible in the restrictions on water infrastructure and water treatment projects as well as the monopoly of Mekorot. Overall, the unfair distribution of water is evident in the following three ways .

I – Restrictions on movement obstruct water access for Palestinians

Territorial fragmentation has resulted in a disjointed and dysfunctional water network in the West Bank. It is estimated that over a third of the water supply is lost. In some towns, water losses are as high as 50% because of leakages from an outdated and neglected water network, inaccurate water metering and illegal connections. Territorial fragmentation is problematic for water supply in all three areas, as effective water management should integrate domestic, agricultural, industrial and environmental needs. This integration is both legislatively and physically fragmented. As Figure 1 shows, Area C isolates Areas A and B, making it difficult to manage Palestinian water infrastructure located in these areas. In addition, fragmentation hinders water projects in Areas A and B because they still require permits from the Israeli authorities to pass through Area C. This frustrates the monitoring of water quality and infrastructure. Furthermore, it is difficult to maintain and rehabilitate infrastructure effectively because of restrictions on movement. As a result of this fragmentation, 46 Palestinian communities in Area C do not currently have access to a (functioning) water network. Consequently, households in these communities have to buy water from trucks. This is 400 times more expensive than water from the network. Moreover, this supply is unreliable because the trucks can be greatly delayed by the many checkpoints they have to pass. People in remote communities, who have to travel longer distances to a water source, are at greater risk of settler attacks.

II – Water reuse is highly constrained

A second cause of water scarcity is that insufficient water reuse infrastructure can be built because Israel denies permit requests. As mentioned above, Israel accuses the Palestinians of mismanaging their domestic water resources, including failing to reduce water losses and increase water reuse. Only 58% of Palestinian permit requests for wastewater treatment projects were granted between 1995-2008. In contrast, 96% of the Israeli requests were granted. In addition, no permits were granted to build water storage tanks or reservoirs in Area C. The Joint Water Committee only granted a limited number of permits to construct new water infrastructure or rehabilitate existing infrastructure. In fact, only 50% of all requests for water infrastructure and rehabilitation projects between 1995-2008 were approved. Reasons for denying a permit to drill a well include that the water source is needed for a future illegal settlement. In contrast, 100% of the requests from illegal settlements in the West Bank were granted.

Currently, only one wastewater treatment plant is operational and less than 3% of the wastewater can be treated because of the denial of permit requests to build additional treatment facilities. Without a permit, donors are unwilling to provide funding because any infrastructure built without permission is at risk of being demolished by the Israel Defense Forces. Consequently, the reuse of treated wastewater is highly constrained. Even though increasing water use efficiency is in itself a positive development, the discourse on alternative sources and higher efficiency is in Israel’s interest. Namely, this discourse means Israel does not have to deal with the overarching problem: Israel taking an unjust share of the water, which is 1.8 times the share agreed in the Oslo II Accord.

III – Mekorot’s monopoly facilitates unfair distribution

A third cause of the water scarcity is the unequal water distribution enabled by Mekorot’s monopoly. Mekorot prioritizes constant water supply for illegal Israeli settlements, frequently cutting Palestinian water supply during the summer by up to 50% and leaving Palestinian households without water for days. This discriminatory treatment is problematic for several reasons. The company has a monopoly on the water network in the West Bank. At the same time, the many restrictions have resulted in Palestinians becoming increasingly dependent on Israel for their water needs. In 2013, almost 50% of the water that Palestinian communities consumed was purchased from Mekorot. According to the Oslo Accords, the Palestinian Water Authority (PWA) is entitled to 31 MCM of water per year from Israel. However, the PWA receives only 75% of this amount and has to buy the rest from Mekorot.

Livelihoods under pressure from territorial fragmentation

The cities of Qalqiliya and Tulkarem illustrate how the discriminatory and fragmented water situation in the West Bank affects people’s livelihoods. Under the Oslo Accords, the cities were designated as Area A but the land around them falls in Area C (Map 2). Consequently, farmers living in Area A have restricted access to water infrastructure and are only allowed on their land in Area C for limited periods of time. In Area C, Palestinians are unable to maintain, rehabilitate or construct any water infrastructure without a permit from the Israeli authorities. This has resulted in: (a) frequent interruption to the water supply for domestic and agricultural use, ranging from a couple of days to two thirds of the year; (b) excessive operational costs due to high expenditure for repairs and fuel prices; (c) insufficient water supply to cover the communities’ needs; and (d) households’ increasing dependency on expensive water tankers, which raises living costs. Together, these issues made the price of water so high that 123 farmers from the cities had to abandon their land.

Israel’s responsibility to protect the human right to water

Israel deprives Palestinians in the West Bank of reliable and safe access to water, which is exacerbated by territorial fragmentation. Israel refuses to take responsibility for this water stress, which leads to the deterioration of people’s livelihoods. The UN Human Rights Council rejects Israel’s stance and has urged it to comply with international humanitarian law. This states that every occupying power has the obligation to respect, protect and fulfil the right to water and sanitation, without discrimination. It is time for Israel to uphold the right to water for everyone in the West Bank.