Photo1: The scarcity of water in Khuzestan results in dust storms (Source:Danial Khodaie).

Author: Ludo Hekman.

This is a translated article. Source:Trouw.nl

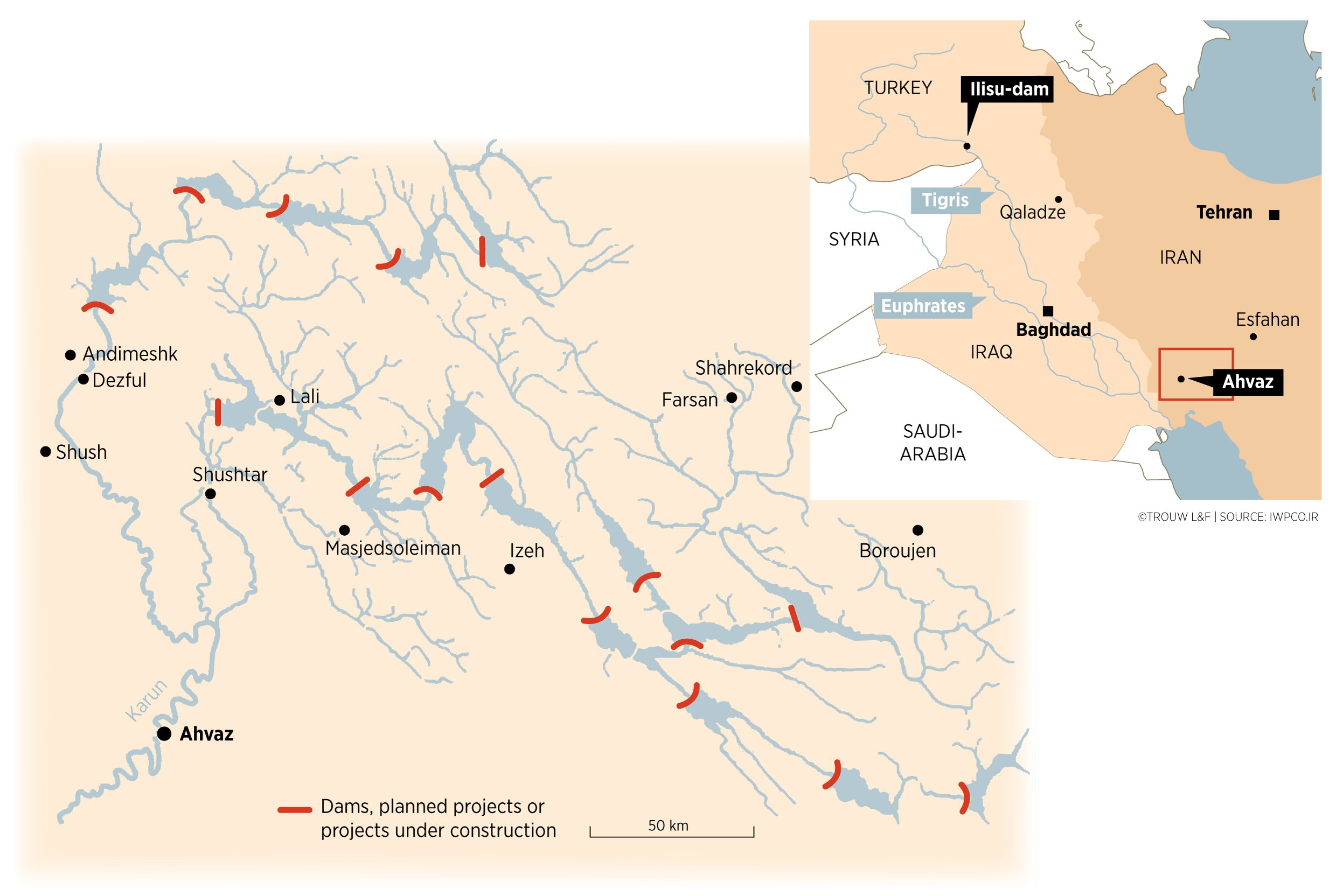

Water scarcity is increasingly fueling conflict in the Middle East, for example, in Khuzestan, in the southwest of Iran. The province literally dried up. One of the main reasons are the dams build in Iran itself and in Turkey.

Khuzestan is an oil-rich province on the border with Iraq. Some 85 per cent of all Iranian oil – the lifeblood of the country’s economy – is extracted here. However, large areas of the province have gone from wetland to wasteland in a matter of years.

The primary reason for this transformation can be found in Iran itself. Although climate change and dam construction in Turkey play a role, Iran is largely to blame for the drought. Dam construction on the Karun river, one of Khuzestan’s most critical water resources, has reduced the water supply by two-third.

The river’s decline is immediately evident in Ahvaz, the provincial capital, which straddles both banks of the river. Between the reeds along the water’s edge are piles of clothes and pieces of cardboard that double as mattresses. Clothes are spread out on the rocks to dry. Strangers are regarded with suspicion and occasionally greeted with hostile shouts. This is where the junkies live, in huts that are somewhere between a garden shed and a bird’s nest. Made from rubbish and reeds, they face towards the water and away from society.

This animation shows how the conflict dams feeds wars in the Middle East.

Former fisherman Abed Divani (60) knows all the addicts and greets them cheerfully. He still regularly takes his boat out on the river and often stops to chat. He has seen the river change. He used to spend long days on the water. He had five boats and caught up to 100kg of fish a day. Everyone in Ahvaz was dependent on the river, he says. “They grew up along its banks, used its water for drinking and agriculture and ate its fish.”

He has not been fishing for three years; there is no point. The fish on the market is now brought in from another province. He drives a pick-up truck and makes small deliveries. The job makes him sad. “But coming to the river every morning and seeing what has happened to it makes me just as unhappy, and angry,” he says. The Karun, once Ahvaz’s beating heart, has become a refuge for people on the margins of society.

The story of the Karun is not unique. The next war will be fought over water, says Abbas Araqchi, a senior diplomat and deputy foreign minister of Iran. The World Economic Forum and the World Bank have made similar predictions, ranking water crises as the most likely to trigger future conflict.

Water scarcity is an important factor in many disputes in the Middle East, and as scarcity increases, so will competition. The enormous growth in the number of dams is a symptom of this. The most powerful countries in the region – Iran and Turkey – have built hundreds of dams in recent decades to meet their water needs. Other countries in the region have paid a high price for this: drought, social unrest and, in the case of Syria, civil war.

Map 1: Location of the dams in Iran.

“In Khuzestan, the changes are now irreversible,” believes Nasser Karami, professor of climatology at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, who grew up in the province. One can no longer speak of drought, he says, because the term suggests that it is a temporary phenomenon. It isn’t. “Khuzestan has dried up.”

Dust storms are not the only consequence of water scarcity. To the north of Ahvaz lies a barren plain. It is hard to imagine that until recently this was lush and green, that you could take a boat through the vast wetland and hear birdsong. The road eventually leads to Arvand Kenar, near the border with Iraq and Kuwait. The area is famous for its date palms, but the further north you go, the more desolate the landscape becomes. Some areas look like they have been hit by a tsunami. All that remains are endless rows of trunks without a crown. The falling water level in the Karun has allowed salt water from the Persian Gulf to penetrate further inland. The increased salinity of the soil is killing the palms.

The impact of water scarcity is also visible to the south-west of Ahvaz, in the Hor al-Azim wetland. Up until the mid-1990s, the depth of water in the wetland could reach ten metres. In the years since, hectare after hectare has been burned or bulldozed for oil extraction. Water buffalo dot the landscape and the reed sheds are evidence that water was plentiful here not so long ago. But of the 40 villages here, not one is still inhabited.

Water scarcity can destabilize entire countries. The clearest example of this is Syria, which lies in the Euphrates basin. Turkey’s dams across the Euphrates, which have increased from 14 in 1980 to 120 today, reduced the flow water into Syria by 20-40 per cent, resulting in drought, dust storms and loss of agricultural land. This drove migration to the city, where poverty and unemployment bred resentment and eventually erupted into demonstrations that sparked the civil war in 2011.

In Iraq too, water scarcity has had a direct impact on the current conflict. This was the conclusion drawn by journalist Peter Schwartzstein, who conducted more than a hundred interviews in Iraq for National Geographic and found that the most water-deprived villages emerged as some of Islamic State’s foremost recruiting grounds.

Could that happen in Khuzestan? The situation is explosive, says Karami. “I expect more demonstrations, and they will be difficult for the government to control. I’m worried about what will happen after that because I expect different types of conflicts. Khuzestan is already vulnerable due to the ethnic and sociocultural tensions, for example between Arab and non-Arab residents. Everyone is asking themselves: how can we be so poor when we live on a sea of oil?”

What makes this particularly painful for that residents of Khuzestan is that the dams on the Karun are not only used for generating energy and irrigating agricultural land, they are also used to channel water via tunnels to other provinces, notably Isfahan in central Iran, which is politically more power. Many residents in Khuzestan feel that their water is being stolen.

Small-scale conflicts over water are already common, and there were recently demonstrations in Ahvaz. But if the residents of Khuzestan could choose between fleeing or fighting, most of them – thanks to the iron grip of the regime – would choose the former. Last year, a leaked study conducted by the provincial government showed that 95 per cent of those surveyed want to leave. In major cities such as Tehran and Isfahan, entire neighbourhoods have sprung up to accommodate migrants from Khuzestan.

Many of the people interviewed for this article are also planning to leave, such as Karim Barodaran (64). He sells fruit and vegetables on the market in Ahvaz’s Arab quarter. “My friends are fishermen but they don’t have jobs anymore. My sons are unemployed.” He is the only wage earner and supports his two sons. “When the water runs out, I’ll have to move to another city or another country. I’m not in a position to change anything, so I’ll have to adapt.”

Morteza Zibaie (28) also sees few prospects in Ahvaz. He works in a shop selling washing machines. The rest of his family has already gone to Isfahan and Tehran. “When my contract expires in six months, I’ll leave too,” he says.

Iran has repeatedly pointed the finger of blame at Turkey, especially since Turkey announced it was pushing ahead with the construction of the controversial Ilisu Dam. Iranian President Hassan Rouhani called the dam dangerous for the whole region and disastrous for Iran.

Photo 3: During a dust storm in Khuzestan resulted by water shortage (Source: Danial Khodaie).

However, Iran is in a difficult negotiating position. Turkey seems determined to complete the Ilisu Dam, despite widespread international opposition, and Iran’s own water management record, which is far from exemplary, leaves it with little leverage. The residents of Qaladze in Iraqi Kurdistan, for example, saw their water supply diminish by 80 per cent in August when an Iranian dam near the border went into operation. The river that was dammed was an important source of water for the Kurdish region.

Moreover, Iran is building its own ‘megadam’ on the Sirwan River, a tributary of the Tigris. The Daryan Dam will reduce the supply of water to Iraqi Kurdistan by 60 per cent, according to calculations by Save the Tigris, an Iraqi NGO that is trying to protect the river.

Reza Ardakanian, Iran’s energy minister, says he wants to review the feasibility and economic impact of all the dams currently under construction. A conference on water diplomacy and crisis management is planned for March 2018, when Iran aims to revise its strategic water position in the region.

Divani, the former fisherman from Ahvaz, does not want to leave. He is too old to migrate, but he sees no future here for his children. “Without the Karun, the city has no meaning.”