Contributors

- Author: Tugba Evrim Maden

- Peer Reviewer: Fanack Editorial Team

Introduction

For many years, negotiations between Turkey and Syria over the Orontes or Asi River[1] were linked to issues concerning the Euphrates and Tigris rivers shared between Turkey, Syria and Iraq, and progress of the former was dependent on progress of the latter. From the start of negotiations between the three countries in the early 1980s, Turkey and Syria adopted conflicting strategies. Whereas, Turkey insisted that negotiations would encompass all regional trans-boundary waters including the Asi, the Euphrates and the Tigris, Syria refused to discuss the Asi River with Turkey. Syria considered the Turkish province of Hatay, through which the Asi River flows before discharging into the Mediterranean, as Syrian territory, and hence regarded the Asi as a national rather than a trans-boundary river. Any negotiation would have been tantamount to acknowledging Turkey’s sovereignty over Hatay.

This stalemate prevailed until Ankara and Damascus signed the Adana Agreement in October 1998. Following this rapprochement, relations between the two countries improved considerably, both politically and economically. During a visit to Syria in 2004, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, then Turkish prime minister, proposed a joint multi-purpose dam to be built on the Asi River.

In 2009, the Syrian Minister of Irrigation and the Turkish Minister of Environment signed a memorandum of understanding for the construction of the ‘Friendship Dam’ on the Turkey-Syria border. The agencies responsible – the Turkish General Directorate of State Hydraulic Works (DSİ) and the Syrian General Company for Hydraulic Studies – met in January 2010 and agreed that the feasibility studies and final design proposal should be ready by October 2010. On 6 February 2011, the prime ministers of both countries celebrated the laying of the foundation stone of the Friendship Dam. However, the project came to a halt with the Syrian uprising in March of that year. Five years on, with no end to the Syrian conflict in sight, the future of the project is now uncertain.

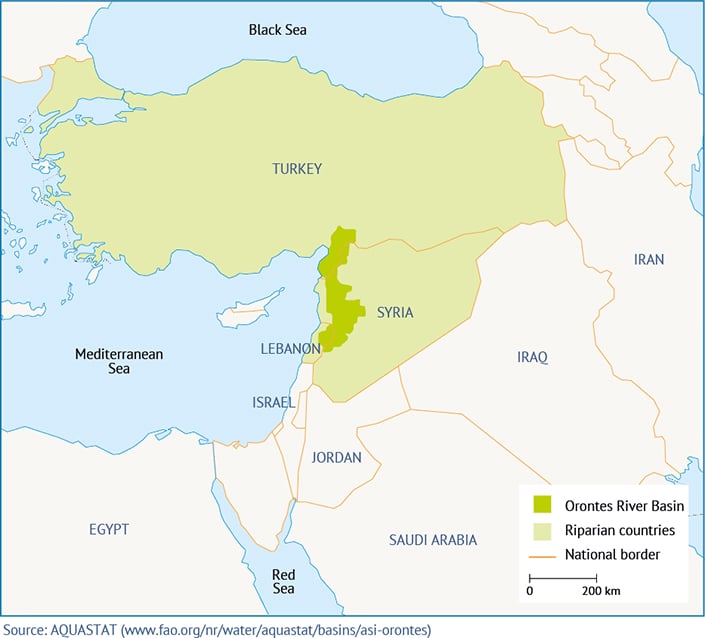

Asi river basin

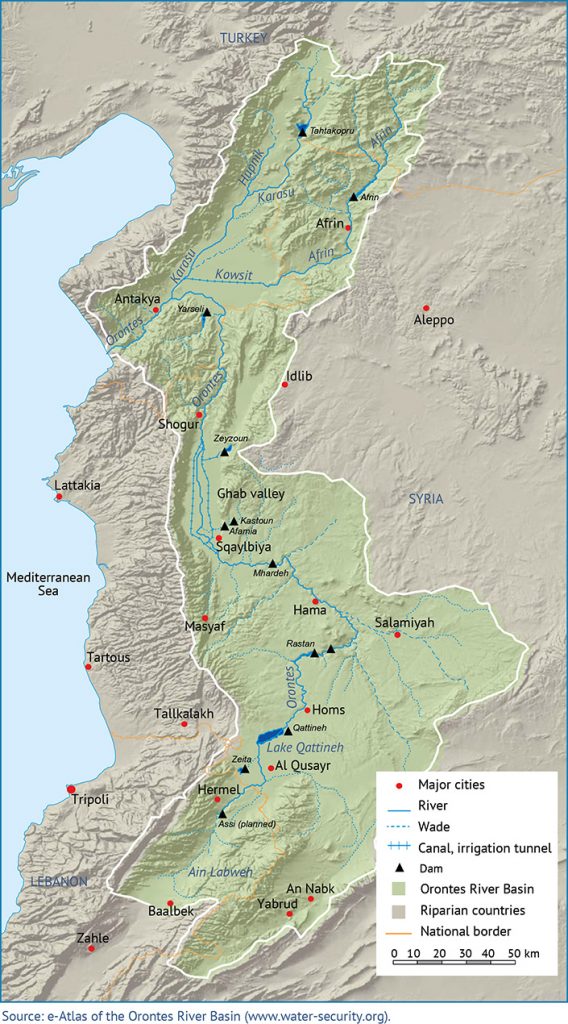

Asi in Arabic means ‘rebel’. Unlike most rivers in the region, which flow from north to south, the Asi River flows from south to north. It rises in the Beqaa Valley in Lebanon and flows northward between Lebanon and the Anti-Lebanon Mountains. Entering Syria near the town of Hermel, it continues to flow northwards past the cities of Homs and Hama and crosses the fertile Ghab Plain. It forms the border between Turkey and Syria for about 31km, turns westward into Turkey and finally discharges into the Mediterranean Sea.[2]

The length of the river is open to discussion. Depending on the source consulted, this ranges from 248km to 556km (see Table 1).

Rainfall in the Asi River basin is about 644mm annually. The average temperature is around 16°C. The climate is semi-arid to arid in Lebanon, with annual rainfall of about 400mm. In the western mountains of Syria, this increases to about 500-1500mm, then drops again to about 400-600mm in the eastern part of the basin. The Turkish part of the basin is a transition zone between the Mediterranean and Eastern Anatolian climatic zones.[9]

The water potential of the river is also disputed. In some sources, this is given as 2.47 billion cubic metres per year (BCM/year).[10]

The most realistic estimate is about 2.8BCM/ year.[11] The groundwater flow is 1.11BCM. The al-Azraq spring makes a significant contribution – approximately 400 million cubic metres (MCM) – to the yearly potential flow. The other major contributors are al-Ghab, al-Roudji and al-Zarqa.[12]

Two major tributaries, the south-flowing Afrin from the west and the Karasu from the east, join the Asi River in Lake Amik. Whereas the Karasu flows in Turkish territory and forms the border between Turkey and Syria for a short distance, the Afrin crosses into Syria before re-entering Turkey. The water potential of the Karasu is 0.39BCM/ year; the discharge rate of the Afrin at the point where it enters Turkey is 0.31BCM/ year.[13]

| Length of river (km) | Reference |

| 248 | Water Problems in the Middle East Report |

| 248 | Orontes River Issues Related with Turkey, Syria and Lebanon |

| 556 | Sustainable Water Management in Hatay: Hydrographic Planning Approach |

| 448 | Orontes River Basin: Downstream Challenges and Prospects for Cooperation |

| 453 | FAO – Irrigation in the Middle East Region in Figures |

| 485 | Syrian Irrigation Ministry |

The Riparians of the Asi river

The Asi River is shared by Lebanon, Syria and Turkey.

Lebanon

Lebanon is the upstream country of the Asi River. It usually experiences intense rainfall in the winter (November-May), but the rest of the year it has a typical Mediterranean climate, with warm, dry weather conditions. Annual rainfall is approximately 800mm.[14]

Some reports indicate that Lebanon is abundant in both groundwater and surface water resources.[15] During the Cold War era, Lebanon could not properly use its water resources due to technological and investment constraints. Lebanon uses a relatively small amount of water – approximately 1.31BCM/year – from the Asi River Basin.[16]

Syria

The annual amount of water used in Syria is about 15BCM. This comes from the Euphrates (50 per cent) and the Asi River basins (20 per cent). Of the water usage from the Asi River, 2,230MCM are used for irrigation, 320MCM for domestic purposes and 270MCM for industrial purposes. The total amount of water withdrawn from the Asi River is 2,730MCM.[17] Seventeen per cent of irrigated land in Syria is within the Asi River Basin. For irrigation, Syria benefits not only from surface water but also from groundwater.[18]

Industrial development is focused on areas where water from the Asi is readily available. The main industrial areas are located in and around Homs and Hama. The amount of water that is pumped from the Asi for industrial use is equivalent to half of Syria’s total water needs. An oil refinery built on Lake Qattinah in 1957, fertilizer production plants built in the west of the lake in 1976 and several olive factories near the Turkish border are major contributors of pollution in the basin. Untreated waste from the olive factories, in particular, is the cause of fish deaths. The water quality is further impacted by agricultural runoff and the inadequacy of the infrastructure in Homs.[19]

The total capacity of the Syrian dams on the Asi River is about 736MCM. The largest of these dams are al-Rastan, Qattinah, Mahardeh, Zeyzoun and al-Qastan. The Homs-Hama channel, which is bound to the Qattinah reservoir, provides water for an area of about 23,000 hectares. The Mahardeh reservoir provides water for the Asharnah Plain and the al-Rastan reservoir provides water for the irrigated areas on the Asharnah and Ghab plains. Planned projects aim to irrigate 72,000 hectares. In areas where the existing reservoir waters are insufficient, groundwater resources are used to irrigate a further 20,000 hectares.[20]

Turkey

Turkey’s gross water potential is 193BCM. The total economically exploitable annual water potential is 112BCM.[21] The Asi River makes up 0.6 per cent of Turkey’s total water potential. Turkey primarily uses the Asi for irrigation, animal farming and drinking water. The area that Turkey would like to irrigate in the Asi River Basin is about 165,000 hectares.[22]

Although Lebanon uses a comparatively small amount of the Asi’s waters, Syria’s Ghab irrigation project mean extremely small amounts of water reach Turkey in the dry months.[23] The General Directorate of State Hydraulic Works (DSİ) drained 23,000 hectares of swamp around Lake Amik in 1972 and opened up these areas to agriculture. However, this project has had negative environmental impacts such as floods and drought.

Turkey has 12 water development projects in the Asi River Basin. Four projects are operational, two are under construction and the remaining six are in the review stage. The projects take into account flood protection, drinking water needs, irrigation and energy. The existing projects irrigate 14,607 hectares of land and produce 170 gigawatt hours (GWh) of energy. When the projects under construction are completed, 8,019 additional hectares of land will be irrigated and 0.95MCM of potable water will be available. On completion of the projects in the review stage, Turkey aims to irrigate 77,489 hectares of land, protect 20,000 hectares from floods, provide about 36.43MCM of potable water and produce 62.77GWh/year energy. When all the projects are completed, a total of 99,575 hectares of land will be irrigated, 180GWh of electricity will be produced, 37MCM of potable water will be provided and 20,000 hectares of land will be protected from floods.[24] Turkey also started building the Reyhanlı Dam near the Syrian border in 2012, which will provide domestic and irrigation water, flood protection and control the groundwater level. Water sources of the dam are the Asi, Afrin and Karasu rivers. The dam will irrigate 60,000 hectares of land and protect 20,000 hectares from floods.[25]

Water use in the Asi river basin and earlier cooperation efforts among the riparians

In all three riparian countries, the river is used mainly for irrigation, domestic water supply and hydropower (see Table 2).

| Riparians | Basin area (km2) | Contribution to annual discharge (BCM) | Main water uses |

| Lebanon | 2,040 | 0.3 | Domestic water supply, irrigation, hydropower |

| Syria | 16,910 | 1.2 | Domestic water supply, irrigation, hydropower |

| Turkey | 5,710 | 1.3 | Domestic water supply, irrigation, hydropower, flood control |

| Total | 24,660 | 2.8 |

The Asi River is diverted to the Homs-Hama water channels and Ghab-Roudji irrigation systems to meet the needs of Lebanon and Syria. The water is also stored in the Zeita Dam for domestic and irrigation purposes and energy production.

Improvement projects in the river basin began in the 1950s. Syria requested financing from the World Bank in order to implement the first large-scale project on Ghab Plain.[29] Accordingly, 30,000-32,000 hectares of swamp were to be drained and converted into irrigated agricultural land. However, the World Bank focused on the international aspect of the project, as it was within a transboundary basin.[30]

It came to the conclusion that the Ghab project would not be affected by Lebanon’s existing water usage, but determined that Syria and this project would be harmed if Lebanon withdrew water in greater amounts.

Figure1.The percentage of basins area riparians of the Asi River. [28]

In addition, as Turkish-Syrian relations at the time were strained, it was expected that Turkey would object on the grounds that the plan did not conform to an agreed settlement of the rights on all rivers shared by Turkey and Syria. Turkey had also previously protested a diversion of water from the Afrin River.[31]

After Turkey had indeed raised objections to the project, the World Bank organized meetings in Damascus with Turkish and Syrian experts. The experts concluded that Turkish territory would be exposed to frequent floods during the construction and that the project as it stood would not leave ‘a drop of water’ for Turkey during the irrigation seasons. In the 1960s, United Nations experts stated that because the headwaters of the Asi River are in Lebanon, Lebanon had the prior right to use about 485MCM per year of the river’s water. In 1962, Syria cooperated with the Netherlands Development Corporation (NEDECO) on a plan to develop the river. However, this failed to take into account Turkey’s position. During a conference between Turkey and Syria, Turkey demanded a draft protocol to be prepared. According to this protocol, the plan would address the interests of and developments in both countries. Necessary flood control measures and review and revision of the NEDECO plan by giving consideration to the above items were also determined. In addition, the water requirements of Lake Amik in Turkey and the establishment of joint stream-gauging and flood-warning stations were determined. However, the conference ended without an agreement being reached on the protocol.[32]

Syria has built various dams on the Asi River, including al-Rastan and Mehordan. One of the biggest was Zeyzoun, which had a reservoir capacity of 71MCM.[33] This dam collapsed in 2002, killing 22 people and damaging homes in Syria and agricultural areas in Turkey. The other large dam is the Zeita, which has a reservoir capacity of 80MCM.[34]

Agreements between the riparians regarding the Asi river basin

The treaty signed between Turkey and France (on behalf of Syria) in 1921, mentions the water apportionment and supply for the waters of Qweik (Kuweik) located between the Asi and Euphrates basins to the south of Aleppo. The Qweik rises in Turkey and has a water potential of 0.2BCM. According to Article 12 of the treaty, the waters of Qweik shall be shared between the city of Aleppo and the district to the north remaining Turkish in such a way as to give equitable satisfaction to the two parties.[35]

The last protocol on the equitable use of the Asi, Karasu and Afrin rivers was signed between Turkey and Syria in 1939.[36]

Water agreements on the Asi River between Syria and Lebanon date back to 1972, after which negotiations stagnated for more than 20 years until a water-sharing agreement was reached in 1994.[37] According to this agreement:[38]

- The Asi River was recognized as rising in Lebanon and being a joint water resource.

- The annual flow of the river was agreed as 403-420MCM.

- Lebanon would receive 80MCM/year of the total of 420MCM and Syria would receive the remaining 340MCM.

- If the annual flow inside Lebanon fell below 400MCM, Lebanon’s share would be adjusted downwards, relative to the reduction in flow.

- The water flow and the amount would be checked by a committee of experts from both countries.

- The main branches and tributaries of the Asi River would be monitored by both countries and the costs of monitoring and repair would be covered by Syria.

- A common arbitration delegation would be established to ensure the implementation of the agreement. Wells in the river’s catchments area that were already operational before the agreement would be allowed to remain operational, but no new wells were permitted.

The agreement was shaped by the demands of Syria, the relatively stronger riparian country, and excluded Turkey entirely.

Turkey-Syria relations: between conflict and cooperation

The Hatay dispute

The name Hatay was given to the region of İskenderun-Hatay by Ataturk in 1936. It was referred to as a “Sanjak” in Turkish and international documents during the Ottoman period. The region was handed over to France by the British as part of the Mondros Armistice Treaty that was signed in 1918. The border between Turkey and Syria and the İskenderun Sanjak was indicated in the French-Turkish Treaty of 1921, and was also adopted in the Treaty of Lausanne, the peace treaty signed on 24 July 1923, after the end of the Turkish war of independence. Following the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne, the French mandate of Syria and İskenderun province entered into force through the League of Nations. While France, the mandatory power, was dividing Syria and Lebanon into four parts, İskenderun was kept away from Aleppo by setting it up as an autonomous Sanjak.[39]

In 1926, a friendship and good neighbourliness contract was signed between France and Turkey. This served to improve relations between Turkey and France as well as between Turkey and the Turks living in the Sanjak. On 9 September 1936, France signed a pre-contract with Syria, which ended France’s mandatory power over Syria. Accordingly, France ceded all its rights and obligations regarding Syria-related agreements, contracts and international pledges. This also affected the status of the Sanjak. Turkey responded angrily, stating that the agreement should have included and been signed by the people of the Sanjak. France objected in turn, and the dispute was brought before the League of Nations. According to the subsequent Sandler Report issued by the rapporteur of The Council of the League of Nations, he offered concerning the Sanjak that a coalition must be formed between Turkey and Syria, and each district must be separate assets on all issues except foreign affairs, customs and common currency. But France did not accept this offer. The committee that was formed according to the report prepared the status of the Sanjak and its constitution and those texts were ratified by the Council of the League of Nations on 29 May 1937.[40]

Turkey and France signed two more agreements in 1937. These covered the issues of international contracts that formed the separate existence of İskenderun Sanjak; ensuring the territorial integrity of the Sanjak; and securing the border between Turkey and Syria.[41]

On 3 July 1938, Turkey and France signed a military agreement. This again affected the Sanjak, because According to the Agreement, territorial integrity and political status of the Sanjak were going to be provided by Turkey and France. During this process, a new friendship agreement was signed between Turkey and France and the validity of the Ankara Agreement from 1921 was reiterated. In the elections held on 22 July 1938, Tayfur Sokmen became the state president in the Grand Assembly, which was opened on 2 September 1938, and the name of the Sanjak was changed to Hatay.[42]

In 1939, upon entering the Second World War, the United Kingdom went in search of an ally in the Mediterranean. It formed an alliance with Turkey, publishing the Common Declaration. However, Turkey wanted to do the same with France and expressed its desire to incorporate Hatay into Turkey. On 23 May 1939, the second step in the tripartite alliance was taken with the publication of the Common Declaration of Turkey and France. On the same day, Turkey and France signed the Agreement on the Absolute Solution for the Territorial Problems between Turkey and Syria. In this agreement, Hatay was included in Turkey. On 29 June 1939, the people of Hatay unanimously agreed to this incorporation, and on 7 July 1939, Hatay province was established and the incorporation process was completed. Syria refused to accept the incorporation, however, and insisted that Hatay was within its boundaries. In protest, it sent a telegraph to both the French government and the League of Nations.[43]

For a long time afterwards, Syria regarded Hatay as its own territory and the Asi as a national rather than a transboundary river. This would persist until well into the 2000s.

The Cold War period

The relations between Turkey and Syria were affected throughout the Cold War era and into the 1990s. The water issue became a foreign relations matter once again when both countries began using the waters of the Euphrates-Tigris basin in the 1960s and building irrigation and energy-related projects. When Turkey, the upstream country in the basin, focused on using the water resources, this caused concern for Syria and the wider Arab world as it was seen as contrary to their own interests and sense of sovereignty.[44] Relations became strained during the construction of the Keban, Karakaya and Atatürk dams on the Euphrates. Syria began to play its cards against Turkey by supporting the PKK (Kurdish Workers Party). In 1983, tensions escalated further when Turkey launched the multi-decade GAP (South-East Anatolia Project).[45] Turkey initially hoped to fund the project with international loans. However, its loan applications were turned down following lobbying by Syria and Iraq and protests from other Arab countries. As a result, Turkey has had to finance the project from its national budget. In 1987, Turkey’s Prime Minister Turgut Özal visited Syria. During the visit, Turkey demanded that Syria cease its support of the PKK and Syria demanded that Turkey sign an agreement regarding the use of the Euphrates. Turkey prepared a protocol pledging to bring about 500 cubic metres per second to Syria from the Turkey-Syria border. Both countries signed the protocol.[46] Furthermore, they signed a security protocol stating that neither country would support any anti-Turkish or anti-Syrian movements within their bounders. Despite this protocol, however, the PKK continued its activities in Syria.[47]

During the Cold War, water and security concerns affected the policies of both countries. As irrigated agriculture was an important part of development, the water issue, in particular, was not just a technical concern but was associated with ideas of identity, self-sufficiency, independence and Arab nationalism. Turkey regarded the water improvement projects that it had started in the Euphrates-Tigris basin as an important investment for Southeast Anatolia where prosperity was low and unequally distributed. Security became one of the most important concerns for the internal policies of both countries, with the PKK playing a leading role in Turkey-Syria relations.[48]

These relations were affected by changes at the global and regional levels in the 1980s and 1990s. The collapse of the Soviet Union, of which Syria was a close ally, left Syria in a particularly disadvantageous position.

In the mid-1990s, reports emerged that the PKK had moved into Hatay. Turkey and Syria came to the brink of war when Turkey threatened military action if Syria continued to support the PKK. This eventually led to the 1998 signing of the Adana Agreement, which stipulated that Syria would not allow ‘any activity that emanates from its territory aimed at jeopardizing the security and stability of Turkey’. Syria also recognized the PKK as a terrorist organization, banned the supply of weapons, logistical material and financial support to the PKK on its territory and expelled Abdullah Öcalan, one of the PKK’s founding members, who had been hosted in Damascus for a decade.[49]

The death of Hafez al-Assad

After the signing of the Adana Agreement, initiatives to improve relations based on mutual trust extended into the 2000s. The attendance of Ahmed Necdet Sezer, then Turkey’s president, at the funeral of Syrian leader Hafez al-Assad on 13 July 2000 was a potent symbol of the countries’ warmer relations. The official visit of Syrian Vice Prime Minister Abdulhalim Haddam to Ankara in 2000 was a turning point in an important, positive process.

The trust that developed between the two countries also allowed for closer economic ties. On 22 December 2004, Turkey and Syria signed their first free trade agreement. As part of the agreement, the neighbours established their borders and Syria officially accepted that Hatay was part of Turkey.[50]

At the same time, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan offered Syria technical support for a proposed joint dam project on the Asi River that aimed to irrigate 10,000 hectares in Syria and 20,000 hectares in Turkey.[51]

Multiple top-level visits cemented the relationship. One of the most significant was the 2004 visit to Turkey of Hafez al-Assad’s successor Bashar al-Assad, the first by a Syrian president since Syria’s independence in 1946. The visit was interpreted as the start of a new period of regional balance and stability.[52]

Turkey and Syria decided to arrange meetings in the framework of The Council of High Level Strategic Cooperation after 16 September 2009. During the Turkish-Syrian First Ministerial Meetings of The Council of High Level Strategic Cooperation, which were held in Damascus on 22-23 December 2009, a total of 50 memoranda of understanding (MoU) and agreements were signed.[53]

The friendship dam

One of the MoUs signed during the meetings was for the construction of a joint Friendship Dam on the Asi River where it crosses the Turkey-Syria border. The foundation stone of the dam was laid on 6 February 2011.

On completion, the dam is expected to be 22.50 metres high, with a capacity of 110MCM. Of that, 40MCM will be used for flood prevention and the rest for energy production (approximately 14GWh annually)[54] and irrigation (around 9,000 hectares of agricultural land).

Table 3. Features of the Friendship Dam.[55]

| Type | Earth-fill dam |

| Drainage area | 16,070 km2 |

| Average yearly flow | 542.15 MCM |

| Total volume (normal + flood) | 114.30 MCM |

| Flood volume | 50 MCM |

| Irrigation area | 8,890 ha |

| Water for irrigation | 47.23 MCM |

| Installed capacity of the hydropower plant | 8.9 MW |

| Average energy production | 13.34 GWh/year |

Recent developments and outstanding issues

The laying of the foundation stone of the Friendship Dam became emblematic of the improved relations between Turkey and Syria and signalled the possibility of greater cooperation in the management of the region’s transboundary waters.

However, the uprising in Syria in March 2011 and the subsequent war have undone much of the progress that had been made in the previous decade. The war has also affected the construction of the Friendship Dam, which has been postponed indefinitely. If the project is finished in the future, the following developments could be realized:

- The inconsistent data on the Asi River, mentioned in the first section, could be corrected by the exchange of information and joint studies.

- A review of the 1994 water-sharing agreement, signed between Lebanon and Syria for the allocation of Asi River waters and from which Turkey was excluded, could include Turkey.

- A review of the water-related initiatives in the Middle East that have been implemented under the guidance of non-riparian countries and have been largely unsuccessful. The example of the Asi River shows that cooperation between riparian countries could be successful.

- Pollution released by agro-industrial plants in Homs and Hama in Syria affects the water quality of downstream users. After the war, this issue could and should be resolved.

[1] Orontes is the English name of the river, whereas Asi is used both in Arabic and Turkish. As such, it will be used throughout this report.

[2] Kibaroğlu, A. et al., 2005. Cooperation on Turkey’s Transboundary Waters. Adelphi Research and the German Federal Ministry for Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety.

[3] Dışişleri Bakanlığı,1994. Ortadoğu’da Su Sorunu. Ankara.

[4] Salha, S., 1995. Türkiye, Suriye ve Lübnan İlişkilerinde Asi Nehri Sorunu. Dış Politika Enstitüsü, Ankara.

[5] Karataş, A., 2015. Sustainable Water Management in Hatay: Hydrographic Planning Approach. Graduate Instituteof International and Development Studies & MEF University, İstanbul.

[6] Scheumann, W.; Sagsen, I.; Tereci, E, 2011. Orontes River Basin: Downstream Challenges and Prospects for Cooperation. Springer, London.

[7] FAO, 2009. Irrigation in the Middle East Region in Figures. Aquastat Survey, Rome.

[8] Maden, T. E., 2011. Türkiye-Suriye İlişkileri: Sınıraşan Sularda Örnek İşbirliği Olarak Asi Dostluk Barajı. ORSAM Rapor, no: 5.

[9] FAO, 2009. Irrigation in the Middle East. FAO Water Reports, no: 34, Rome.

[10] Toklu, V., 1999. Su Sorunu, Ululararası Hukuk ve Türkiye. Turhan Kitabevi, Ankara.

[11] Scheumann, W.; Sagsen, I.; Tereci, E, 2011. Orontes River Basin: Downstream Challenges and Prospects for Cooperation. Springer, London.

[12] FAO, 2009. Irrigation in the Middle East Region in Figures. Aquastat Survey, Rome.

[13] Kibaroğlu, A. et al., 2005. Cooperation on Turkey’s Transboundary Waters. Adelphi Research and the German Federal Ministry for Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety

[14] Fanack Water of the Middle East and North Africa, 2016. Lebanon Country Report. Available at https://water.fanack.com/lebanon/.

[15] Salha, S., 1995. Türkiye, Suriye, ve Lübnan İlişkilerinde Asi Nehri Sorunu.

[16] Lebanon Country Fact Sheet. Available at www.fao.org/nr/water/aquastat/data/cf/readPdf.html?f=LBN-CF_eng.pdf (18/03/2016).

[17] Salman, M.; Mualla, W., 2008. Water Demand Management Syria: Centralized and Decentralized Views. Available at ftp://ftp.fao.org/agl/iptrid/conf_egypt_03.pdf (19/03/2016).

[18] Ibid.

[19] Caponera, D. A., 1993. ‘Legal Aspects of Transboundary River Basins in the Middle East: The Al Asi (Orontes), The Jordan and The Nile’. Natural Resources Journal, XXLIII, no. 3, pp. 629-663.

[20] Canatan, E., 2003. Türkiye-Suriye Arasında Asi Nehri Uyuşmazlığ. Yayımlanmamış Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Ankara.

[21] DSİ, 2014. DSİ and Water. DSİ, Ankara.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Gürol, M. D.; Bayar, S. (eds.), 2009. Sınıraşan Sular ve Türkiye. Gebze, GYTE.

[24] Strategic Foresight Group, 2011. Blue Peace Plan: Rethinking Middle East Water.

[25] DSI, 2012. ‘Suriye Sınırındaki Reyhanlı Barajı’nda Çalışmalar Tüm Hızıyla Devam Ediyor’. Available at www.dsi.gov.tr/haberler/2012/08/15/reyhanlibaraji (15/07/2016).

[26] FAO, 2009. Irrigation in the Middle East Region in Figures. Aquastat Survey, Rome.

[27] Scheumann, W.; Sagsen, I.; Tereci, E, 2011. Orontes River Basin: Downstream Challenges and Prospects for Cooperation. Springer, London.

[28] FAO, 2009. Irrigation in the Middle East Region in Figures. Aquastat Survey, Rome.

[29] Kibaroğlu, A. et al., 2005. Cooperation on Turkey’s Transboundary Waters. Adelphi Research and the German Federal Ministry for Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety.

[30] Caponera, D. A., 1993. ‘Legal Aspects of Transboundary River Basins in the Middle East: The Al Asi (Orontes), The Jordan and The Nile’. Natural Resources Journal, XXLIII, no. 3, pp. 629-663.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] FAO (no date). Aquastat, Main Database, Dams. Available at www.fao.org/nr/water/aquastat/dams/index.stm.

[34] UN-ESCWA and BGR (United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia; Bundesanstalt für Geowissenschaften und Rohstoffe), 2013. Inventory of Shared Water Resources in Western Asia. Beirut. Available at

[35] Karpuzcu, M.; Gürol, M. D.; Bayar, S. (eds.), 2009. Sınıraşan Sular ve Türkiye. Gebze, GYTE.

[36] Kibaroğlu, A. et al., 2005. Cooperation on Turkey’s Transboundary Waters. Adelphi Research and the German Federal Ministry for Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety.

[37] Scheumann, W.; Sagsen, I.; Tereci, E, 2011. Orontes River Basin: Downstream Challenges and Prospects for Cooperation. Springer, London.

[38] Salha, S., 1995. Türkiye, Suriye ve Lübnan İlişkilerinde Asi Nehri Sorunu. Dış Politika Enstitüsü, Ankara.

[39] Oran, B. (ed.), 2001. Türk Dış Politikası: Kurtuluş Savaşından Bugüne Olgular, Belgeler, Yorumlar, Cilt 1: 1919-1980. İletişim Yayınları, İstanbul.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Altunışık, M.B., Tür Ö., 2006, ‘From Distant Neighbours to Partners? Changing Syria-Turkish Relations’. Security Dialogue, SAGE Publications, vol. 37, no. 2.

[45] Olson, R., 1995, ‘Turkey-Syria Relations Since the Gulf War: Kurds and Water. Journal of South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, vol. XIX, no. 1 (fall).

[46] Olson, R., 1995. ‘Turkey-Syria Relations Since the Gulf War: Kurds and Water’. Journal of South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, vol. XIX, no. 1 (fall).

[47] Ibid.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Larrabee, F.S., 2007. ’Turkey Rediscovers the Middle East’. Foreign Affairs, July/August.

[50] Kibaroğlu, A. et al., 2005. Cooperation on Turkey’s Transboundary Waters. Adelphi Research and the German Federal Ministry for Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety.

[51] Ibid.

[52] Larrabee, F. S., 2007. ‘Turkey Rediscovers the Middle East’. Foreign Affairs, July/August.

[53] Ayhan, V., 2009. ‘Türkiye-Suriye İlişkilerinde Yeni bir Dönem: Yüksek Düzeyli Stratejik İşbirliği Konseyi’. Ortadoğu Analiz, vilt 1, sayı 11, p. 27. Turkish Republic Ministry of Interior, Press Briefing, no: 2009/107.

[54] Selek, B., 2014. Presentation, Water Resources Development and Management in Turkey with Specific Reference to the Asi River Basin. Republic of Turkey, Ministry of Forestry and Water, General Directorate of State Hydraulic Works.

[55] Ibid.