Author: Bouran Awad is a senior water resources engineer at Newtech Consulting Group, Sudan. She specializes in water infrastructure development and water security studies, and she also serves as an expert for CIMA Research Foundation.

Introduction

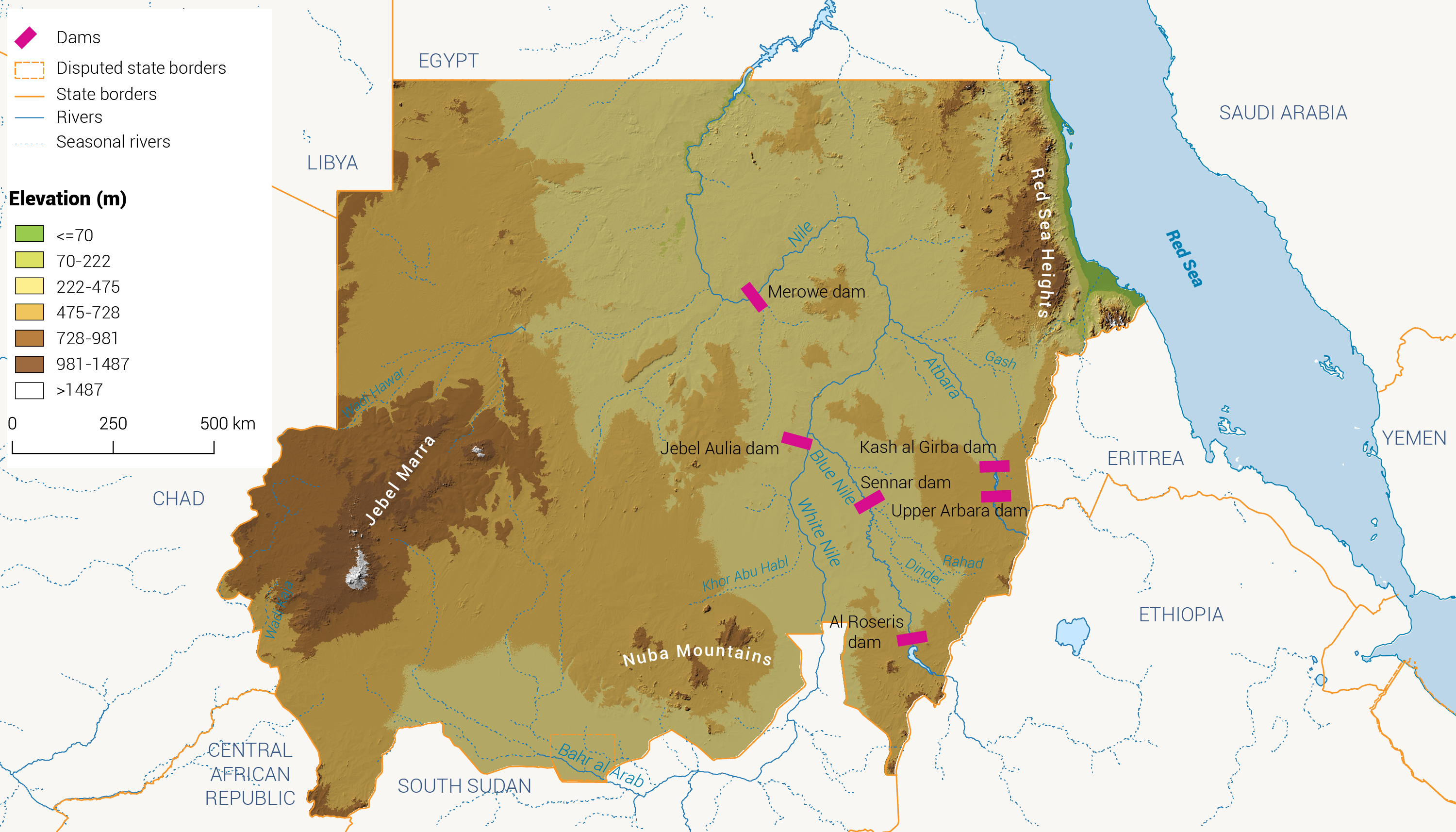

In Sudan, the chronic political instability and widespread conflict have cast a shadow over attempts at institutional reform. The situation is further exacerbated by Sudan’s so-called ‘resource curse’, a paradoxical situation in which a country underperforms economically despite being home to valuable natural resources. The most volatile sector? Water. As a resource of utmost strategic importance, water has been both a source and a casualty of Sudan’s persistent armed conflicts. This article delves into the role of water resources in Sudan’s war-torn history. It also looks at the impact of these conflicts on water resources management, shedding light on the fragile institutional and legal structure and the lack of robust governance. In addition, it explores the complex dynamics of water infrastructure development, which can serve as either a stabilizing force or a catalyst for conflict. Finally, it discusses the significance of maintaining a delicate balance between the principles of ‘do good’ and ‘do no harm’ when planning for water infrastructure in areas plagued by instability and conflict.

Background

The recent turmoil resulting from conflicts within Sudan’s military government has significantly impacted the lives of thousands of Sudanese citizens in the capital Khartoum and other areas. As basic amenities become inaccessible, people are seeking refuge in neighbouring states and countries. With Khartoum’s central role in business, industry and law, the crisis has widespread implications, not least for water resources. These alarming events underline the need for effective plans to rebuild and implement significant institutional and legislative reforms, both federally and at the state level.

In general, efforts to carry out institutional reforms in Sudan have been hindered by political instability, such as the secession of South Sudan in 2011, which further strained the economy. Adding to the woes are the ethnic and social conflicts that have burdened successive governments, making it almost impossible for the country to break free from its resource curse. Throughout Sudan’s history, water resources have played an important role in political tensions as well as armed conflicts. The water sector is one of the most strategic sectors in every country. In Sudan, water is both a trigger and a target of armed conflicts.

An overview of Sudan’s conflicts

Two main conflict types plague Sudan. The first revolves around territorial disputes along the country’s borders, while the second stems from ethnic tensions among nomadic groups, frequently intensified by disputes over cattle and grazing land. Both forms of conflict are often inflamed by disagreements over shared water resources, a scenario worsened by the scarcity of water in Sudan’s desertified regions.

One of the driving forces behind the last civil war between the north and the south was the Jonglei Canal. The plans did not include much improvement in the lives of the people along the proposed canal and in the south, and the project was halted in 1983 following the outbreak of the north-south conflict.

On the other hand, armed conflicts in Sudan could disrupt water systems that are crucial for human and environmental well-being. Water resources have been underutilized in conflict-affected states for decades. As a result of poor governance of water and weak institutions, state governments in conflict-affected areas are unable to develop sufficient capacities to manage their own water sector during the reconstruction process.

A UN Environment Programme (UNEP) report indicates that the violence in many states is causing people to turn to armed groups as a last resort because most of these states have been without functioning civilian-led governments – governments that can restore state authority throughout the country. This increases competition for natural resources, further fuelling migration and displacement.

Although it is generally believed that several peace agreements have been signed, notably the Juba Agreement for Peace in 2020, tensions remain in many states, especially in Darfur, South Kordofan and the Blue Nile. There has been ongoing unrest in these states related to power, wealth and the sharing of natural resources, issues that have not been adequately addressed by these peace agreements.

Water crisis in conflict-affected sub-states

Darfur, in Western Sudan, has been ravaged by conflict over grazing lands and water scarcity. The water crisis in North Kordofan and other western states has been exacerbated by the arrival of displaced people fleeing violence in Darfur and West and South Kordofan. Furthermore, drought and desertification have forced many people from the northern part of the state to relocate.

In eastern Sudan, the Butana region has suffered from droughts for decades. In 2019, after the ruling Transnational Military Council blocked water supplies, a dispute erupted in El-Gadarif between two groups competing for fresh water. Given the groups’ different ethnic backgrounds, the dispute escalated into an ethnic conflict, resulting in one death and a number of injuries.

In the past year, the ethnically diverse eastern state of Kassala has also witnessed a dispute related to a water project, although it has experienced recurrent conflicts over natural resources for decades. Likewise, inter-communal violence has been a persistent issue in South Sudan’s Blue Nile state since the signing of the Juba Agreement for Peace. UNEP warns that escalating conflicts may hinder adaptation to climate change among vulnerable communities.

Water crisis in Sudan extend beyond quantity to quality. The recent clashes in Khartoum and resulting breakdown of the water treatment plant there have forced families to use untreated Nile water for drinking and other purposes.

Interventions

Several projects and initiatives were launched in the country to assist with conflict resolution. The European Union funded the Wadi El Ku Integrated Catchment Management Project (2013-2017), which was implemented by UNEP in partnership with Practical Action, communities, and the state government of North Darfur. A major benefit of the project was improved food security, livelihoods and agricultural productivity. Additionally, the project reduced tensions and prevented disputes between communities over scarce natural resources, particularly between pastoralists and crop farmers.

Some projects have been confronted with challenges that were not considered in the projects’ initiation. For example, Zero Attash (‘zero thirst’) was initiated in fragile states to develop a mechanism for implementing water harvesting projects and thereby relieve pressure on the Nile River. However, the project failed to conduct comprehensive stakeholder consultations, eliciting opposition from some states. In addition, the suspension of the project in 2019 was attributed to the economic crisis that led to the failure of the Central Bank of Sudan to pay periodic dues. Consequently, Arab donors blocked funding for the project.

Supply-demand gaps and conflict

In the Middle East and North Africa, water conflicts often arise from a significant discrepancy between water supply and demand. Despite rising water demand in Sudan, many disputes stem not only from resource scarcity but also from poor governance, ineffective institutions and unclear delegation of authority.

Ineffective management has led to inconsistent estimates of water demands by various institutions. This, in turn, has resulted in the production of redundant and conflicting studies that have led to disorganized, unreliable planning and allocation of water resources.

Additionally, Sudan’s water sector faces a severe brain drain, with a lack of qualified staff capable of designing, implementing and managing water resources [1]. Political interference and subsequent staff turnover have further reduced institutional memory and capacity to guide the sector.

In terms of legal provisions, there is no law governing water management or assigning a regulatory role to the Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation. Sudan also lacks an endorsed water policy, and its existing laws do not provide guidance for using water resources efficiently, productively and sustainably.

According to the most widely cited Water Law (1995) and a draft Water Policy (2007), several gaps exist, which have caused a decline in the agriculture and water sectors in the past decades. These gaps can be attributed to the lack of cohesive policies and strategies that have resulted in inadequate investment, research and capacity-building programmes as well as internal conflicts and instability, particularly in the western and eastern agricultural centres.

The absence of a prioritization plan for water demand, especially among warring and ethnically diverse communities, is one of the most significant triggers for water conflicts. Coordination of competing demands through dialogue between the various stakeholders is rarely considered.

Another trigger for water-related disputes is local communities seeking projects that yield tangible results in a short period of time. Tribal administrations usually look for immediate political victories to strengthen their positions in the areas where they operate. Pressure to implement will, however, result in more conflict and ownership issues. This could be reinforced by the marginalization of minority groups as community leaders may be afraid of losing power if they share the responsibility of planning and managing water resources. It is worth mentioning that the power balances between different community groups and with different government actors is also influenced by changes in the broader political context.

Balancing water infrastructure and peace

Water infrastructure contributes to the stabilization of fragile and conflict-affected states, reduces conflict, increases local security and restores access to markets by extending state authority.

Nevertheless, water infrastructure may become a legitimate target during conflicts since it symbolizes state power or facilitates military access. In conflict-prone regions, the scorched earth strategy exacerbates the deterioration of basic infrastructure, leaving famine, disease, displacement and devastated livelihoods in its wake. Furthermore, stalemating public services on purpose or through the destruction of water facilities is a counter strategy used by the ruling regime or warring parties as a way of suppressing enemies and their allies.

Projects specifically funded by several agencies in western Sudan have rekindled social conflicts in many states, with citizens claiming ownership and obsessive pursuit of land and water resources. Therefore, site selection for the construction of water infrastructure may be controversial and should consider the conflict context.

Conclusion

Sudan’s water crisis illuminates the fragile intersection of resource management, political instability and social conflict. Despite the daunting challenges, solutions exist in comprehensive, long-term strategies that consider the complexities of the nation’s social fabric. Effective water governance requires not just a focus on infrastructure development but also on the root causes of conflict, encompassing ethnic tensions, territorial disputes and resource distribution.

Addressing these root causes requires strengthening institutional capacities, implementing sustainable water policies, and instigating robust legal frameworks for water management. Moreover, fostering community dialogues can help bridge ethnic divides, encourage cooperation and prioritize water demand, thereby mitigating conflict.

Lastly, as Sudan seeks to overcome its resource curse, it must adopt the principles of ‘infrastructures for peace’, ensuring that every step towards resource development also contributes to lasting stability. The nation’s journey is emblematic of the intertwined challenges of conflict, climate change and resource management. Therefore, its lessons hold valuable insights for other countries navigating similar issues.

[1] Ministry of Irrigation and Water Resources (2021). Sudan Water Sector Livelihoods Transforming Strategy (2021-2031). Khartoum, Sudan: Ministry of Irrigation and Water Resources.