Contributors

- Authors: Niloofar Sadeghi is Programme Officer for Natural Sciences, UNESCO Tehran Cluster Office.

- Peer Reviewer: Majid Kholghi, is a Professor in Irrigation and Reclamation Engineering Department, Director of Groundwater Research Institute, University of Tehran, Iran.

The Zayandehroud, which means ‘life-giving river’, is the largest river in central Iran and has traditionally been a major source of water for the country. Like many great rivers, the ancient city of Isfahan flourished around the Zayandehroud. Isfahan has about 1.8 million inhabitants, making it the third largest city in Iran and home to some of the world’s finest architecture. One of the highlights is its legendary series of Safavid-era bridges.

Zayandehroud, which flows from the Zagros Mountains in the west and once provided fertile fishing and inspiration of many poets, has been replaced by mud and stones. The only evidence that it was once a great waterway are the bridges and paddle boats docked on its dusty banks. People blame different factors for the river running dry, but the main ones are noticeably less rainfall and ever-expanding irrigation plans. The dry-up of the river has caused agriculture to be abandoned in many parts of the basin and led to farmer protests and, in some cases, migration.

The basin currently faces several challenges, including overuse of both the surface water and groundwater in the catchment area, frequent dust storms, desertification and conflict over water use. It is expected that climate change will exacerbate the situation due to higher temperatures and less precipitation. Unless a holistic approach is taken towards the water management of the entire catchment area, and residents and farmers are committed to consume less, the Zayandehroud River will disappear completely.

Characteristics of the Zayandehroud Basin

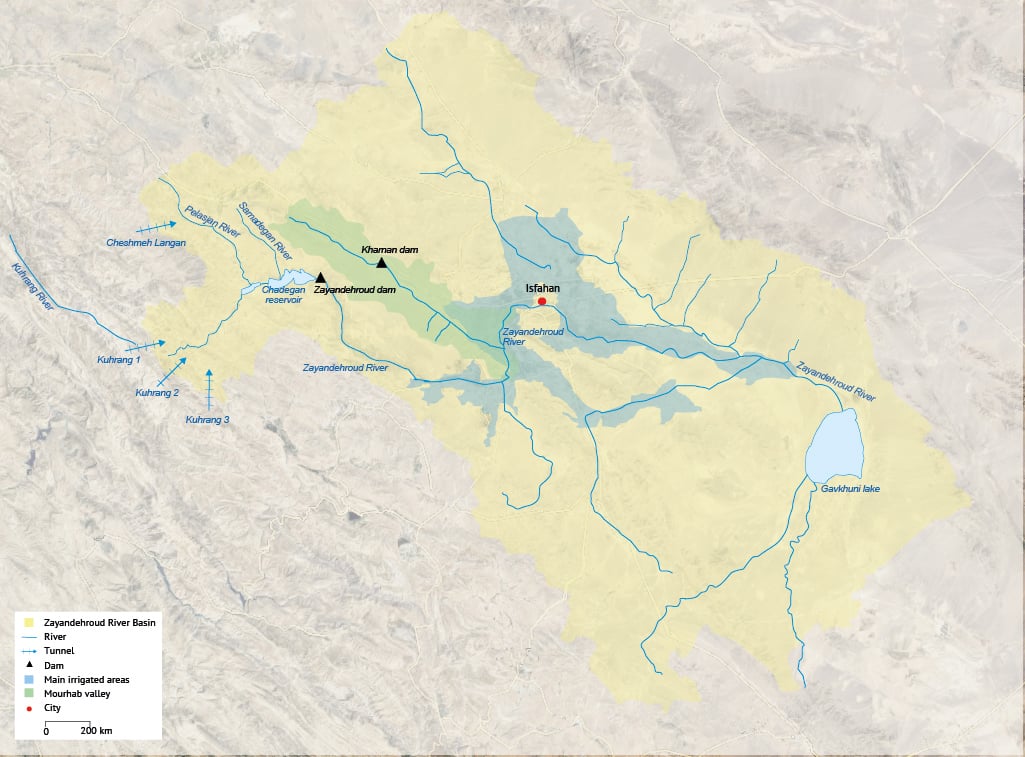

The Zayandehroud Basin covers 41,500km2 in central Iran and includes three main rivers: Zayandehroud River, Pelasjan River and Samandegan River[1]. The Zayandehroud River rises in the bleak and craggy Zagros Mountains, which reach over 4,500m, traverses the foothills in a steep, narrow valley and then bursts forth onto the plains at an altitude of some 1,800m. The river eventually empties into the Gavkhuni Lake, a vast expanse of white salt that forms the bottom end of the basin, although it still lies at an altitude of over 1,200m. In this naturally confined basin, the flows reaching the lake are now much reduced compared with natural conditions, and there are extended periods when no water at all flows in the tail reach of the river.

The total length of the river is some 360 km (Table 1) and so the catchment encompasses many different climatic and ecological conditions. It is the central 150km of the floodplain to the east and west of Isfahan that provides the basis for intensive agriculture and large settlements. Along this strip, soils are deep and fertile, predominately silts and clay loams, and slopes are gentle, ideal for the irrigated agriculture built up over many centuries. The river indeed forms an oasis in the desert.

The primary source of water in the basin is, thus, the upper catchment of the Zayandehroud (see table 1). Run-off generated in the upper basin is strategically stored in the Chadegan reservoir, constructed just above the point where the Zayandehroud enters the flatter parts of the basin (map 1). From September through to February, inflows only average between 50-75 million cubic metres (MCM) per month (20-30m3/s), reflecting both the dry conditions of the summer and the cold conditions dominated by accumulation of snow in the upper parts of the basin. From March onwards, snowmelt increases and discharges normally peak in April or May, with average flows of 125-150m3/s. In June and July, the discharge slowly declines to low-flow conditions. The peak flows from April to June provide the basis for widespread downstream irrigation using simple diversion structures.[3]

| Length (km) | Annual stream flow (MCM) | Monthly min. temperature of area (°C) | Monthly max. temperature of area (°C) | Monthly average temperature of area (°C) | |

| Zayandehrud River | 360 | 858 | -9 | 24.7 | 10.13 |

| Pelasjan River | 72.5 | 122 | -10 | 24.7 | 10.04 |

| Samandegan River | 26.9 | 7 | -10 | 26.5 | 11.51 |

Table 1: Characteristics of the Zayandehrud basin.[4]

Early Water Use in the Zayandehroud River Basin

Water use around Isfahan is as old as the city itself, with records of water management dating back to the 3rd century BC. Riparian rights in the 16th century are described in detail in a tumar (edict), which is attributed to Sheikh Bahai, one of the scientists of that time. The tumar specifies the amount of water apportioned each month to each boluk (district) and village. In other words, Sheikh Bahai mathematically designed a just water distribution system in this region. His system was used for a long time and everybody was very satisfied with it.

The Khaju, Siosepol and almost all the other Safavid bridges in Isfahan were built to function as both crossings and dams to regulate the water flow in the river. Today, they span an often waterless river. Since they were designed to be submerged, the lack of water may damage their foundations.

Until a few decades ago, the groundwaters of the Zayandehroud basin were sustainably managed through qanats (an ancient water-supply system that taps underground mountain water and channels it downhill). However, since the introduction of tube wells in the 1970s, the qanats system has been abandoned and overexploitation of groundwater in the basin has increased significantly.

Current Situation in Zayandehroud River

The population in the Zayandehroud basin has increased dramatically in the past 55 years. According to the 1956 census, the population in the basin was around 420,000; in 2011, that number had reached an estimated 4.5 million.

Agricultural and urban development in the basin has always been constrained by water availability. However, the history of the basin’s water development is not (yet) a story of limits. Demand – largely generated by expansion of irrigation schemes – has always exceeded supply, despite the successive increases in available water brought about by reservoirs and inter-basin transfers. However, ‘new’ water has, each time, been committed outright.[5] Figure 1 illustrate the water demand by sector, where agricultural activities use the largest percentage amongst the other sector.

Figure 1: Water demand by sector in Zayandehrud Basin.[6]

The basin’s resources were first augmented in 1953, when an inter-basin tunnel diverted water from the Kuhrang River to the Zayandehroud basin, adding 340MCM/yr to a natural runoff of about 900MCM. In 1970, the completion of the 1,500MCM-capacity Chadegan reservoir (see Figure 1) allowed the regulation of the water regime. Thanks to these two projects, water supply and storage in the basin dramatically increased. This date also almost coincides with the nationalization of water resources in 1968 (and the establishment of regional water authorities, subordinate to the Ministry of Energy), signalling the new power acquired by the state to control the lifeblood of the region and to design the expansion of the irrigation area in the valley, where an area of 76,000 hectares provided with modern hydraulic infrastructure was established. Yet, in many cases, these modern schemes were superimposed on the ancient network of maadi (canals) and qanats. Thus, the gains were limited, although double cropping became possible in most of the valley.[7]

With the opening of a second inter-basin tunnel from the Kuhrang River in 1986, another 250MCM was made available annually. The increased available supply, in addition to being committed to new irrigation areas, also met the growing needs of Isfahan (with its population now totalling 1.6 million, and a growth rate that reached 5% in some years) and of neighbouring industries. In 2010, an additional 260MCM was made available through the third Kuhrang tunnel, together with 200MCM diverted from the Dez River upper catchment (the Lenjan tunnel).[8]

With all these development projects, one would expect the water needs of Isfahan to be fully met and agriculture to flourish in the watershed. However, water was committed to cities located in much drier areas (Yazd, Rasfanjan, Kashan) and outside the basin.

Despite the periodic transfer of additional water from neighbouring basins, there is a constant over-commitment of water resources within the basin. ‘Donor basins’ complain about the diversions, claiming that they are not based on sound scientific analysis. The imbalance that results from interbasin water transfers is also attributed to political concerns.[9]

In 2014, the issue of insufficient flow, particularly in the summer, led to a series of protests. About 1,000 farmers in the east of Isfahan province drove their tractors 100km to the city and destroyed valves on pipelines carrying water to Yazd. There was further unrest in the spring of 2014, when farmers threatened additional protests if the river stayed dry. Although the central government in Tehran promised the farmers that the river would flow in the autumn, securing plant cultivation, those who benefitted from the previous government’s policies are reluctant to give up their gains.[10]

The damage in Isfahan province has been substantial. Analysts say tens of thousands of hectares of farmland have turned to desert. Many trees have died over the past years and land has subsided – a by-product of draining groundwater supplies, threatening the city’s historical sites, notably the bridges.

The already severe water scarcity is being exacerbated by farmers’ careless use of the available irrigation water in the Zayandehroud basin. This is due to generous government subsidies that provide low agricultural water tariffs that has encouraged the wasteful use of a resource long taken for granted. Growing competition over water has led to overexploitation of groundwater resources across the province, which has more than 60,000 wells (of which 15,000 are illegal).

By lowering the water table, well users (including those in the city who sank deep wells to irrigate large ‘green belts’ of trees planted ‘for the environment’) not only tap underground flows that used to contribute to the base flow of the river but also ‘drag’ water from the riverbed to lateral aquifers, to the detriment of irrigation downstream of Isfahan.[11]

Given the critical situation of the Zayandehroud basin, the government has embarked on several initiatives to revive the basin. The most important of these are: holding two rounds of stakeholder consultations attended by over 5,000 farmers; establishing a special task force composed of various line ministries to revive the Zayandehroud River and Gavkhuni Lake; developing a basin restoration plan; banning the cultivation of water-intensive crops; holding

As the Zayandehroud River has dried up, a 5,000-year-old civilization is on the verge of disappearing. The situation requires urgent action by every citizen in the basin as well as neighbouring basins. Although the government is introducing measures to balance water demand, the solution to restoring the basin lies in the cooperation and commitment of residents and farmers.

What Does the Future Hold for Zayandehroud River?

While the annual yield of the Zayandehroud River has been significantly increased as a result of water transfers in the past decades, the basin is still suffering from serious water shortages. Overexploitation (due to an abstraction rate far above available resources) and reallocation (whether implicit or explicit, intended or not) are due to both the lack of monitoring of who gets what and when, and the absence of a system of entitlement or rights.[12] The situation is likely to worsen as a result of climate change. On average, the monthly temperature in the basin is expected to increase by 0.46-0.76°C and annual precipitation is expected to decrease by 14-38%, resulting in a reduction of the Zayandehroud’s peak stream flow and the extent of its seasonal range.[13]

The negative impacts of climate change on water resources, coupled with increasing water demand, will intensify the current water scarcity in the basin. Adaptation strategies must be implemented to ensure sufficient supply and efficient consumption of water in response to new hydrological conditions.[14] Adaptation can be defined as the adjustments that are applied in natural and human systems to exploit beneficial opportunities or reduce risk and damage from current or future harms.[15]

A basin-level coordination mechanisms is needed to analyse hydrological data, establish transparent allocation schemes, discuss priorities and development plans, and integrate representatives from the different socio-economic sectors. This is currently being addressed by the Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) Project supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). The project is tied to the first phase of the IWRM project in Isfahan, which started in 2010 and finished in February 2015. As a result of the second phase of the project, a decision support system, based on a water management tool, which was developed in the first phase, will be devised to initiate the IWRM process.[16]

Any reform in the water sector of the Zayandehroud Basin requires financial resources, the availability of which in an economy still struggling under international sanctions is questionable.

[1] Safavi, H.R., Golmohammadi, M.H., Sandoval-Solis, S. (2015). Expert knowledge based modeling for integrated water resources planning and management in the Zayandehrud River Basin. Journal of Hydrology, 528, 773-789.

[2] Molle, F. et al. (2009). ‘Buying Respite: Esfahan and the Zayandehroud River Basin, Iran’. In River Basin Trajectories: Societies, Environments and Development. Comprehensive Assessment of Water Management in Agriculture Series 8. Molle, F. and Wester, P. (eds)

[3] Ibid.

[4] Safavi, H. R. et al. (2015). Expert knowledge based modeling for integrated water resources planning and management in the Zayandehrud River Basin. Journal of Hydrology, 528, 773-789. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282301749

[5] Molle, F. et al. (2009). ‘Buying Respite: Esfahan and the Zayandehroud River Basin, Iran’. In River Basin Trajectories: Societies, Environments and Development. Comprehensive Assessment of Water Management in Agriculture Series 8. Molle, F. and Wester, P. (eds).

[6] Safavi, H. R. et al. (2015). Expert knowledge based modeling for integrated water resources planning and management in the Zayandehrud River Basin. Journal of Hydrology, 528, 773-789. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282301749

[7] Molle, F. et al. (2009). ‘Buying Respite: Esfahan and the Zayandehroud River Basin, Iran’. In River Basin Trajectories: Societies, Environments and Development. Comprehensive Assessment of Water Management in Agriculture Series 8. Molle, F. and Wester, P. (eds).

[8] Molle, F. et al. (2009). ‘Buying Respite: Esfahan and the Zayandehroud River Basin, Iran’. In River Basin Trajectories: Societies, Environments and Development. Comprehensive Assessment of Water Management in Agriculture Series 8. Molle, F. and Wester, P. (eds).

[9] Molle, F., Mamanpoush, A. (2012). Scale, governance and the management of river basins: A case study from Central Iran. Geoforum, 43(2), 285-294.

[10] Financial Times, 2014, Iran: Dried out, https://www.ft.com/content/5a5579c6-0205-11e4-ab5b-00144feab7de

[11] Molle, F. et al. (2009). ‘Buying Respite: Esfahan and the Zayandehroud River Basin, Iran’. In River Basin Trajectories: Societies, Environments and Development. Comprehensive Assessment of Water Management in Agriculture Series 8. Molle, F. and Wester, P. (eds).

[12] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2001). Climate Change 2001: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. IPCC third assessment report. Cambridge University Press, London.

[13] Gohari A., Bozorgi A., Madani K., Berndtsson R. (2014). Adaptation of surface water supply to climate change in central Iran. Journal of Water and Climate Change, 5 (3).

[14] Financial Times, 2014, Iran: Dried out, https://www.ft.com/content/5a5579c6-0205-11e4-ab5b-00144feab7de

[15] Molle, F. et al. (2009). ‘Buying Respite: Esfahan and the Zayandehroud River Basin, Iran’. In River Basin Trajectories: Societies, Environments and Development.

[16] For more information about the project, please see www.iwrm-isfahan.com/en/home/home.php.