Renewable water resources in Algeria are estimated at approximately 19 billion cubic metres per year (BCM/yr) (Table 1), approximately 450 cubic metres (m3) per capita per year. This is below the recommended 500 m3 per capita per year recognized as the scarcity threshold indicating a water crisis [1]. Water resources are characterized by high variability.[2]

| Water resource | Volume (BCM) | Region |

| Renewable surface water | 11 | North and south |

| Renewable groundwater | 2.5 | North |

| Non-renewable groundwater | 6.1 | South |

Table 1: Water resource availability.[3]

Surface water (Main rivers; availability since 1950)

Algeria is divided into five major river basins comprising a total of 17 catchments and concentrated mainly in the north (Map 1). The renewable surface water resources are estimated to total 11 BCM.[4]Surface water inflows are low in the Saharan basin, with a total of 0.5 BCM per year. In contrast, the north relies mainly on surface water, since almost 7 BCM is captured by a number of medium and large dams. Runoff occurs as rapid and powerful floods that replenish the dams during the short rainy season, which typically runs from December to February.[5] [6]

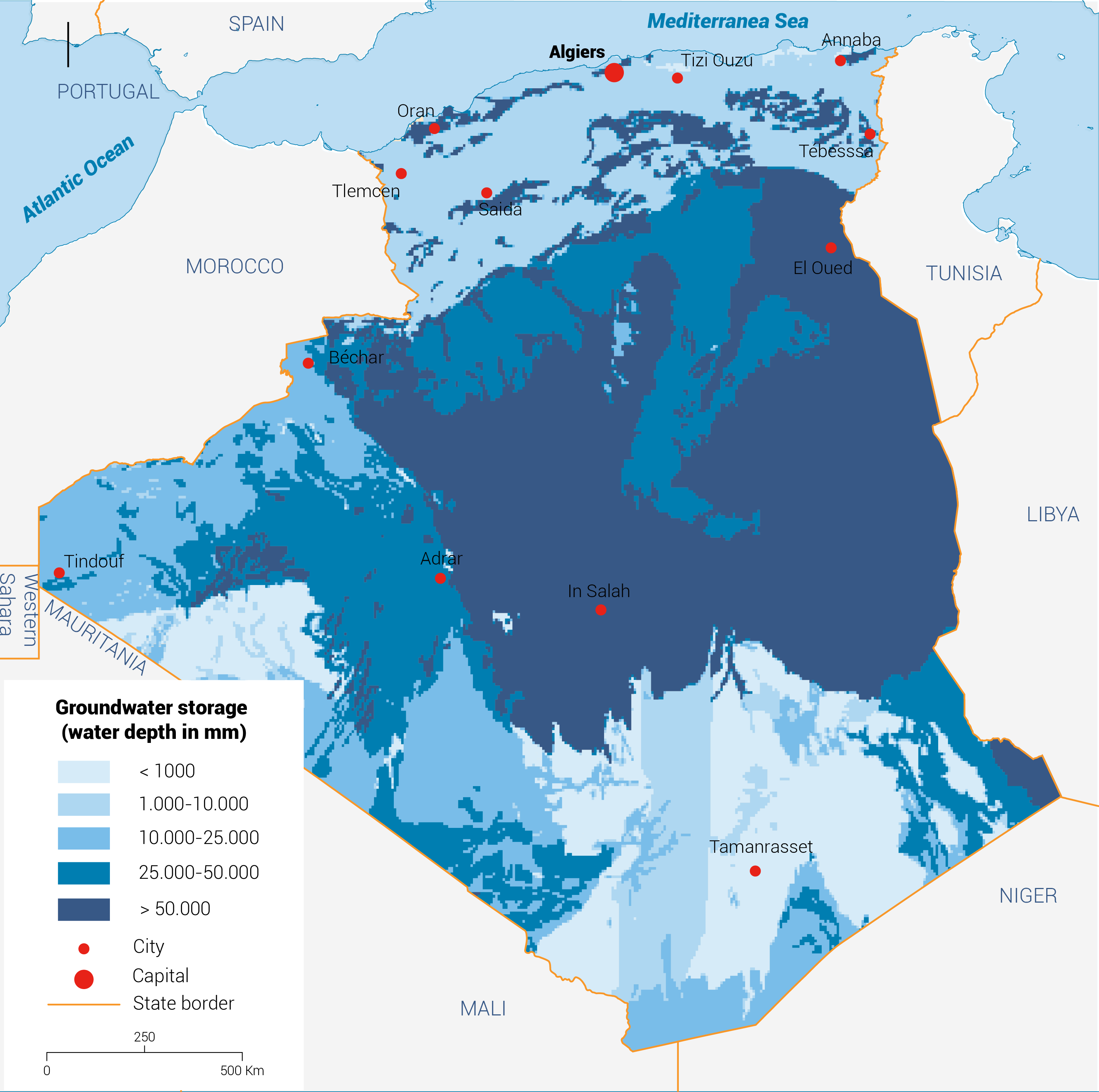

Groundwater (Main aquifers/springs; availability since 1950)

Groundwater resources are estimated to total 7.6 BCM, but demand is much higher in the north of the country. Important aquifers in the Sahara meet 96% of water demand in the south.[7]

In the mountainous region in the north, the aquifers are shallow and exploited using wells and springs. While these aquifers are naturally recharged with 1.9 BCM/yr, the total withdrawals are estimated at 2.4 BCM/yr. The deficit is mainly due to a lack of effective groundwater management, linked to poor knowledge of the resource, an increase in the number of illegal wells and a lack of coordination between the water authorities.[8] [9]

Groundwater in the south is mainly fossil with very low renewability. The water resources are contained within two major overlapping aquifers, the Complex Terminal and the Continental Interlayer, which form the transboundary North-Western Sahara Aquifer System (NWSAS). The Complex Terminal (100-400 metres deep) and the Continental Interlayer (1,000-1,500 metres deep) contain significant reserves of 30,000-40,000 BCM (Map 2). The deep aquifers are exploited mainly using deep boreholes, whereas the shallow ones are exploited using the traditional foggara system.[10]

Non-conventional sources (Desalination; wastewater reuse; rainwater harvesting)

Comparing supply and demand shows a current water deficit of 1.3 BCM. The projected population growth almost certainly means this deficit will grow, necessitating a new strategy for seawater desalination and wastewater reuse.

Desalination

With 1,622 km of coastline, Algeria has begun desalinating seawater to supply drinking water to cities and towns located up to 60 km away from the coast. In 2016, the country had 11 large desalination plants in operation capable of producing up to 2.21 million cubic metres of desalinated water per day (MCM/d) (Table 2).

The commissioning of two other stations will bring the total production capacity to 2.3 MCM/d by 2020.[11] [12]

| Stations | Small | Big | Total |

| Number | 21 | 9 | 30 |

| Capacity (MCM/d) | 57,500 | 1,410,000 | 1,467,500 |

| Production (MCM/yr) | 21 | 514.6 | 535.6 |

Table 2: Seawater desalination stations since 2013.

Wastewater reuse

The reuse of treated wastewater has become a priority in the new water policy, resulting in the rehabilitation of old stations and the construction of new ones. The aim is to build 239 wastewater treatment plants with a total capacity of 1.2 BCM/yr of purified water mainly intended for irrigation, thereby preserving traditional water resources while increasing agricultural production.[13]

[1] Rapport d’Information déposé en application de l’article 145 du Règlement par la Commission des Affaires Étrangères de France en conclusion des travaux d’une mission d’information constituée le 5 octobre 2010 sur La géopolitique de l’eau, 2011.

[2] Hamiche A, Stambouli A and Flazi S, 2016. ‘A review on the water and energy sectors in Algeria: Current forecasts, scenario and sustainability issues’. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 41:261-276.

[3] Ibid

[4] GIZ/BGR/OSS, 2016. Projet CREM: Etude d’évaluation du secteur de l’eau en Algérie, Etat des Lieux.

[5] Ibid

[6]Hamiche A, Stambouli A and Flazi S, 2016. ‘A review on the water and energy sectors in Algeria: Current forecasts, scenario and sustainability issues’. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 41:261-276.

[7] Bouchekima B, Bechki D, Bouguettaia H, Boughali S and Tayeb Meftah M, 2008. ‘The underground brackish waters in South Algeria: Potential and viable resources’. Laboratoire de Développement des Energies Nouvelles et Renouvelables dans les Zones Arides Sahariennes, Université de Ouargla.

[8] British Geological Survey, 2018. Africa Groundwater Atlas: Hydrogeology of Algeria.

[9] Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2009. Groundwater Management in Algeria: Draft Synthesis Report.

[10] Ibid

[11 ] GIZ/BGR/OSS, 2016. Projet CREM: Etude d’évaluation du secteur de l’eau en Algérie, Etat des Lieux.

[12] Safar-Zitoun M, 2018. Plan National Secheresse Algerie: Deuxième Version. Convention des Nations Unies de Lutte contre la Désertification.

[13] Mozas M and Ghosn A, 2013. État des lieux du secteur de l’eau en Algérie. IPEMED.