Dams

Iraq’s extensive reservoir network is at the heart of the country’s ability to manage its water resources. The dams are operated in three independent systems: System No. 1 covers most of the country, encompassing the Euphrates, Tigris, Greater Zab and Lesser Zab; System No. 2 encompasses the Adhaim watershed; and System No. 3 encompasses the Diyala watershed (Map 1). Each system is operated to manage the water distribution to municipal, industrial, agricultural and environmental users and to provide downstream flood hazard protection.

Besides water storage and flood protection, some dams are also used for hydropower production. The three largest hydropower dams in Iraq have a combined installed capacity of around 2,100 megawatts (MW), including the Mosul Dam with 1,050 MW, Haditha Dam with 660 MW and Dokan Dam with 400 MW. However, the actual hydropower generation is usually significant lower, due to low water levels in the reservoirs and operational constraints.[1]

Mosul Dam, Iraq’s largest dam with a capacity of 11 km³, poses a significant flood threat. The dam was built over beds of gypsum, which can dissolve without regular grouting. If erosion were to undermine the dam, its collapse could flood parts of Mosul within a few hours and Baghdad within days, threatening millions of Iraqis.[2]

In March 2016, the Italian company Trevi was hired, together with the US Army Corps of Engineers, to carry out a grouting project to stabilize the dam. The project, which cost $530 million, involved drilling more than 5,200 holes and grouting almost 40,000 m³ of cement mixture into the subsoil that supports the dam. This work stabilized the dam enough to allow for a water level flow of 321 m, the highest level in over ten years.[3] The project was completed in June 2019.[4]

Although the project was of high priority to address pressing safety concerns, the dam requires this kind of maintenance continuously. Additionally, it is unclear how much flood protection the dam can provide even after the project. While being able to operate at 321 m is an improvement, previous studies have shown that the dam would need to operate at its full capacity of 330 m to provide effective flood protection.[5]

Flood control

Despite the construction of dams in Turkey and Syria, it is still possible for flooding to occur in Iraq, particularly along the tributaries to the Tigris such as the Greater Zab, which is the last undammed large river in Iraq.[6] Some of the other smaller eastern tributaries also lack flood control infrastructure and are known to experience flash flood events.

Presently, flood peaks are managed using the storage capacity of on-stream dams and barrages as well as some off-stream topographic depressions. The Tigris is regulated by Mosul Dam and Dokan Dam on the Lesser Zab (a tributary to the Tigris) and Samarra Barrage. In case of extreme events where the Mosul and Dokan dams are not able to reduce flood peaks to acceptable values for the Baghdad reach, Samarra Barrage is the next point downstream that can manage flows coming from the upstream reservoirs (in addition to flows entering from the Greater Zab), and can divert water to Tharthar Lake.[7] Haditha Dam and Ramadi Barrage regulate flows on the Euphrates. Ramadi Barrage can divert flows from the Euphrates to Habbaniyah Lake, and Majarra canal conveys flows from Habbaniyah Lake to Razzazza Lake in the event of large flood events.[8]

Derbendikhan Dam, on the Diyala, is similarly regulated, attenuating floods to protect Baghdad. The Diyala flows into the Tigris just downstream of Baghdad. Due to a backwater effect, simultaneous floods on the Tigris and Diyala could pose a flooding risk to Baghdad. In the upstream part of the Diyala, Derbendikhan Dam regulates the flow on the river. The dam’s normal operating rules can be overridden to store more water behind the dam and prevent floods from reaching Baghdad.[9]

Irrigation systems

Two thirds of the 6 million hectares of cultivated land in Iraq are irrigated (Map 2). Of these, 63% are irrigated via gravity canals, 36% receive irrigation water via pumps from rivers or major canals, and 1% are irrigated with groundwater from springs or pumped up from aquifers.[10]

Medium- and large-scale irrigation projects can be found along Iraq’s rivers, including extensive irrigation canals and pumping systems. The country’s major irrigation projects include the Jazeera Irrigation Project in Nineveh governorate, which draws water directly from the Tigris and the Mosul Dam reservoir and will irrigate more than 1 million dunam (1 dunam = 0.1 hectares) when fully developed; the combined Kirkuk-Adhaim-Hawija Irrigation Project with more than 1 million dunam of irrigated land, drawing water from various tributaries to the Tigris, including the Lesser Zab; the Middle Tigris Project, which covers more than 1.5 million dunam on both sides of the Tigris between Baghdad and Kut; and the Great Abu Ghraib Project, the largest irrigation project along the Euphrates, irrigating more than 500,000 dunam between Fallujah and Baghdad.[11]

Throughout the country, irrigation infrastructure is largely outdated and in disrepair, including both pumping stations, most of which were built in the 1970s and have been insufficiently maintained since then, and canals.[12] A 2015 survey of 50,000 km of irrigation canals found that only around 20% of canals are lined with concrete, leading to significant water losses.[13]

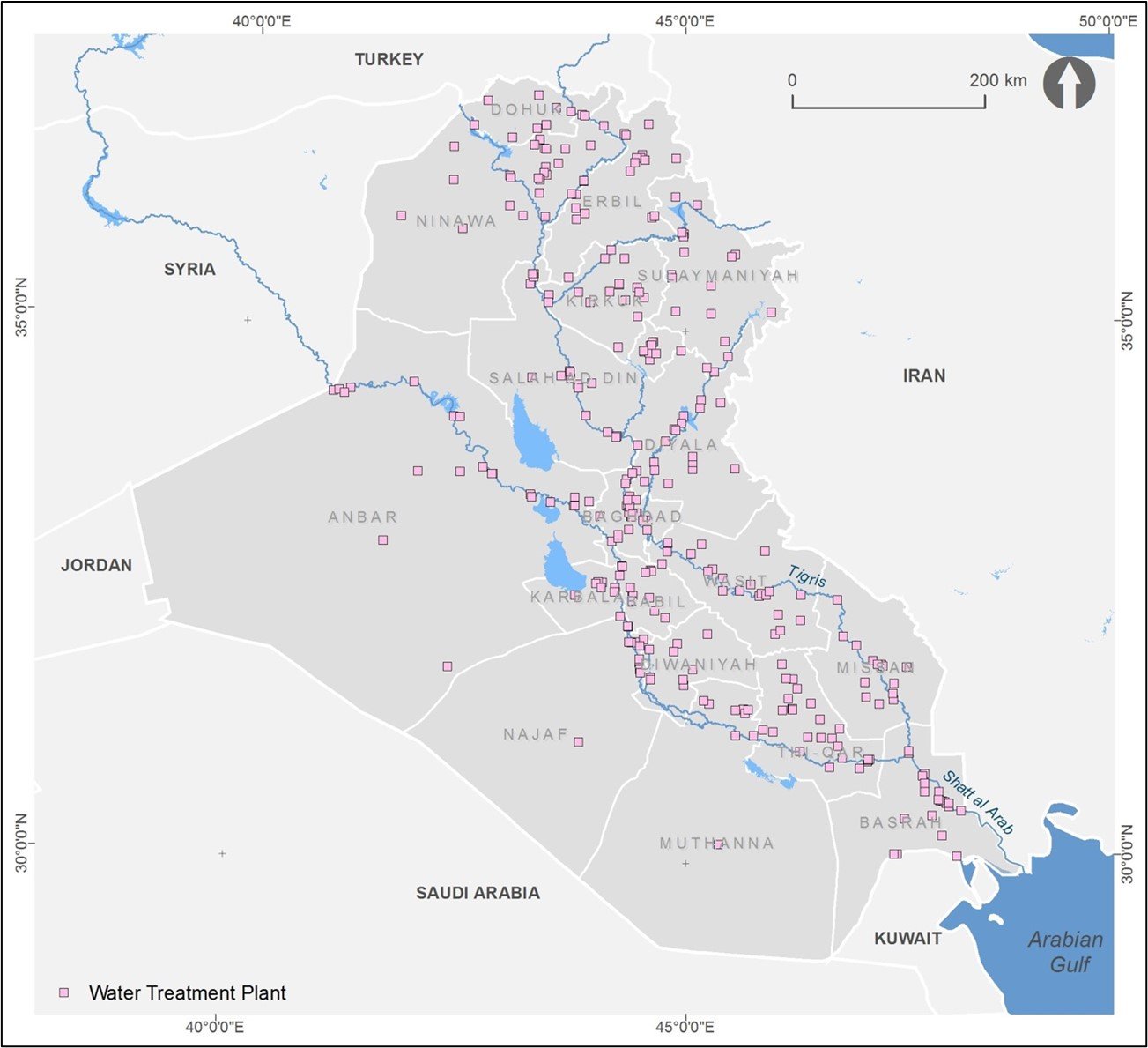

Water treatment infrastructure

Water treatment services do not currently reach all Iraqis. Approximately 86% of the urban population and approximately 62% of the rural population have access to an improved water source via the country’s water distribution network.[14] Iraq’s water treatment infrastructure consists of water treatment plants (Map 3), compact units and solar plants that are used to treat both surface and groundwater sources. The daily production of drinking water is currently around 12.5 million cubic metres per day (MCM/d). Baghdad governorate can treat more than 3.5 MCM/d whereas most other governorates can treat no more than 1 MCM/d, and many can treat no more than 0.5 MCM/d.[15]

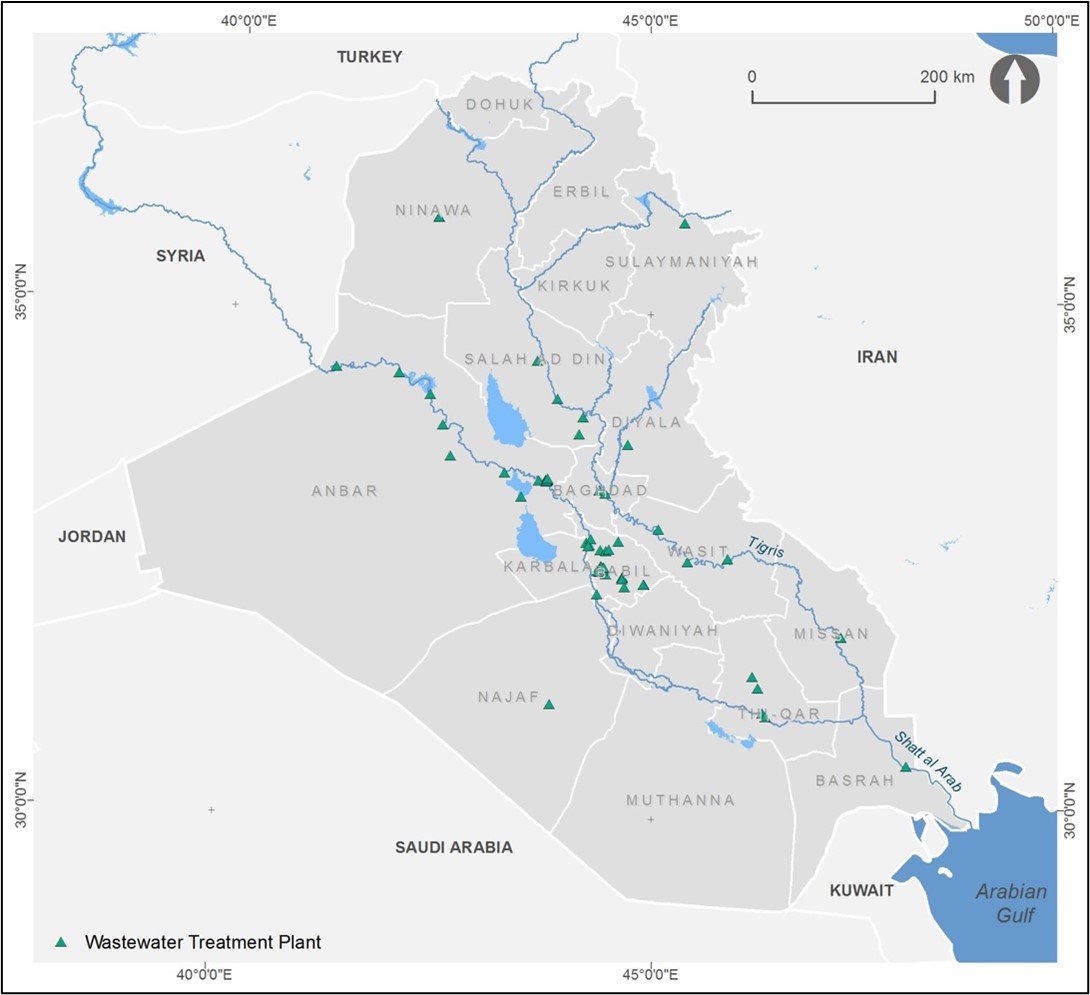

Sanitation and wastewater treatment infrastructure

Approximately 30% of Iraq’s population has access to a sanitary sewer system and, of the 18 governorates, only ten have wastewater treatment facilities.[17] Access to sewer systems tends to be concentrated in urban areas where wastewater treatment facilities are available. This means that most rural areas do not have access and therefore resort to alternate means of discharging sewage (e.g. underground septic systems or discharging untreated waste into channels or rivers). The spatial distribution of wastewater treatment plants is illustrated in Map 8.

Baghdad’s sewer network serves approximately 78% of the governorate, but for the remaining governorates that have treatment facilities, the extent of the sewer network covers less than 30% of the area, and in some cases, less than 10%.[19] The public health implications of these conditions are dire, exposing the population to pathogens and other contaminants that enter the water supply as untreated wastewater drains to freshwater sources. Between 2007 and 2012, at least three outbreaks of cholera were reported, and for each of the years between 2007 and 2010, more than 44,000 cases of typhoid, bacillary dysentery and hepatitis B were reported.[20] In 2012, at least four people died as a result of cholera outbreaks in northern Iraq.[21]

Traditional water systems

Iraq, particularly northern Iraq, is rich in karez, subterranean aqueduct systems also known as qanats, aflaj, foggara or khettara in other parts of the Middle East. They are traditional groundwater management systems, dating back centuries or, in some cases, millennia.

In modern times, karez often compete with groundwater wells and cease to function as the groundwater table drops due to overpumping. Additionally, karez require a significant amount of maintenance to ensure that all tunnels remain functional and free of debris. The combination of these two factors has led to the abandonment of many karez in Iraq.[22]

[1] Ahmad-Rashid, K, 2017. ‘Present and future for hydropower developments in Kurdistan’. Energy Procedia 112: 632-639.

[2] Garland, C, 2019. ‘Army wraps up Mosul Dam mission, the ‘construction project that never ends’’. Published by Stars and Stripes on 21 June 2019.

[3] Trevi, n.d. Mastering the task: Mosul Dam project.

[4] Ingram, E, 2019. ‘Trevi return Mosul Dam to the Iraqi technicians, but this dam is effectively a construction project that never ends’. Published by Save the Tigris on 30 June 2019.

[5] This issue was studied extensively for the national water strategy, and it was found that the dam would need to operate at 330 m to offer full flood protection. Ministry of Water Resources of Iraq, 2014. Strategy for Water and Land Resources of Iraq 2015-2035.

[6] The Rashava-Deralok Dam is a gravity dam currently being constructed on the Great Zab River, just upstream of the town of Deralok in Dohuk governorate, Kurdistan Region of Iraq. The dam will support a 37.6 MW run-of-the-river hydroelectric power station, with the primary purpose being to address continued power shortfalls in the region. See Iraq Project Series: Deralok Hydropower Plant Construction Project (Overview) video, posted 23 January 2020.

[7] Ministry of Water Resources of Iraq, 2014. Strategy for Water and Land Resources of Iraq 2015-2035.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Mohammed, S, 2018. ‘The importance of fixing Iraq’s irrigation’. Published by 1001 Iraqi Thoughts on 6 July 2018.

[11] Abdullah, M and Al-Ansari, N, 2020. ‘Irrigation projects in Iraq’. Journal of Earth Sciences and Geotechnical Engineering 11(2), 2021: 35-160.

[12] Mohammed, S, 2018. ‘The importance of fixing Iraq’s irrigation’. Published by 1001 Iraqi Thoughts on 6 July 2018.

[13] Japan International Cooperation Agency, 2016. Data Collection Survey on Water Resource Management and Agriculture Irrigation in the Republic of Iraq.

[14] Ministry of Planning/Central Organization for Statistics and Information Technology (COSIT), Ministry of Municipalities and Public Works, Ministry of Environment, Baghdad Municipality, Ministry of Planning/Statistics Office of the Kurdistan Region, Ministry of Municipalities of the Kurdistan Region, Ministry of Environment of the Kurdistan Region, in cooperation with UNICEF, 2011. Environmental Survey in Iraq 2010: Water-Sanitation-Municipal Services.

[15] Ministry of Water Resources of Iraq, 2014. Strategy for Water and Land Resources of Iraq 2015-2035.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ministry of Planning/Central Organization for Statistics and Information Technology (COSIT), Ministry of Municipalities and Public Works, Ministry of Environment, Baghdad Municipality, Ministry of Planning/Statistics Office of the Kurdistan Region, Ministry of Municipalities of the Kurdistan Region, Ministry of Environment of the Kurdistan Region, in cooperation with UNICEF, 2011. Environmental Survey in Iraq 2010: Water-Sanitation-Municipal Services.

[18] Ministry of Water Resources of Iraq, 2014. Strategy for Water and Land Resources of Iraq 2015-2035.

[19] Ibid.

[20] United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2014. Integrated Drought Risk Management National Framework for Iraq: An Analysis Report.

[21] World Health Organization, 2012. Cholera in Iraq.

[22] Lightfoot, D, 2009. Survey of Infiltration Karez in Northern Iraq: History and Current Status of Underground Aqueducts. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.