In a largely arid country like Libya, clean water is most valuable for meeting human needs and agricultural production. Contamination from seawater intrusion and oil drilling has put water quality under pressure and reduced the useable supply. Consequently, water quality is considered a critical issue.

Surface water quality

As stated in the previous section, surface water resources in Libya– from springs or captured in dam reservoirs– are highly restricted and contribute less than 3% of the total water resources in use. Most of the springs are of good water quality.[1] However, a small number have salinity levels that make them unsuitable for drinking. These are the Benghazi and Tobruk springs at Jabal al-Akhdar, Tawargha, Wadi Ekaam and Heshin Gefara and Nafusa/Hamada.

Groundwater quality

Groundwater quality, represented by the total dissolved solids (TDS), varies across basins. The data presented is the only information that exists, since no periodic monitoring is conducted across Libya.

Murzuq Basin: The shallow aquifers, usually tapped by hand-dug wells, have salinity (TDS) ranging from 1,000 to 4,000 milligrams per litre (mg/L), which may increase to more than 5,000 mg/L in the vicinity of sabkhas. The deep aquifers, which are tapped by drilled wells, have very low salt content ranging from 100 to 200 mg/L.[2]This situation presents an important risk of water from shallow aquifers mixing with that from deeper aquifers due to vertical downward leakage.[3] [4]

GefaraPlain

Quaternary-Pliocene-Miocene aquifer: The water quality of these aquifers is good, with TDS less than 1,000 mg/L. The areas along the coast between Sabratah and Zawiyah and the immediate surroundings of Tripoli are affected by seawater intrusion, resulting in an increase in groundwater salinity of more than 5,000 mg/L.[5]

Abu Shayba sandstone aquifer: TDS in these aquifers is normally good, ranging from 1,000 to 2,000 mg/L.[6]

Azizia aquifer: Generally, the water quality is medium to poor, with TDS ranging from 2,000 to 4,000 mg/L.[7]

Kufra and Sarir: The quality of water in these basins is represented by the water drawn from wells in Kufra. Water quality is excellent, with TDS ranging from 150 to 250 mg/L. Shallow aquifers may have higher salinity due to evaporation in the sabkhas.[8] Mesozoic sandstones produce good quality, with TDS less than 500 mg/L, except the upper part of the aquifer in areas where the water level is close to the surface. Oil wells drilled in Palaeozoic aquifers indicate that this water is fresh, with TDS less than 1,000mg/L.[9]

Jabal al-Akhdar: The quality of groundwater throughout this area normally varies from 450 to 3,000 mg/L. Some aquifers in the basin show variations in quality even in the same aquifer owing to the complexity of the carbonate marine depositional system. Hydrogen sulphide is common in some localities while others have high concentrations of hardness in the water. The northern coastal area of the basin suffers from seawater intrusion as a result of an increase in groundwater exploitation. For this reason, the salinity of the coastal aquifer is rising.[10]

A recent study indicated that deep aquifers in central Libya contain hot sulphuric water (42-80 degrees Celsius) with some metallic minerals (magnesium and iron).[11] The study concluded that this type of water could be used for curative purposes, according to American health specification standards.

Sanitation and wastewater treatment network

Libya’s Bureau of Statistics and Census estimated the urban and rural populations supplied by sanitary networks to be 45%, while 54% are served by onsite septic tanks. Sanitary networks are equipped with more than 6,000 kilometres of sewage collection/transport pipelines.[12] Since 1971, more than 70 WWTPs have been constructed, another numbers are either under contract or under construction to serve more than 400 urban and semi-urban areas. At present, only 19 plants are operating adequately, producing 200,000 m3/d. WWTPs are designed to produce effluents suitable for agricultural irrigation, using modified activated sludge treatment technology in large cities, whereas on-site oxidation ponds are employed in rural or remote locations.[13]

Access to better sanitation across Libya has improved gradually in the last decades. According to an AWC/CEDARE report, access to safe sanitation rose from 85% in 1990 to 97% in 2005.[14]

Construction, operation and maintenance of sanitation networks are currently financed solely by public funds, although it is hoped that allowing private sector involvement in the sector organization will change this.[15]

Environmental and health risks

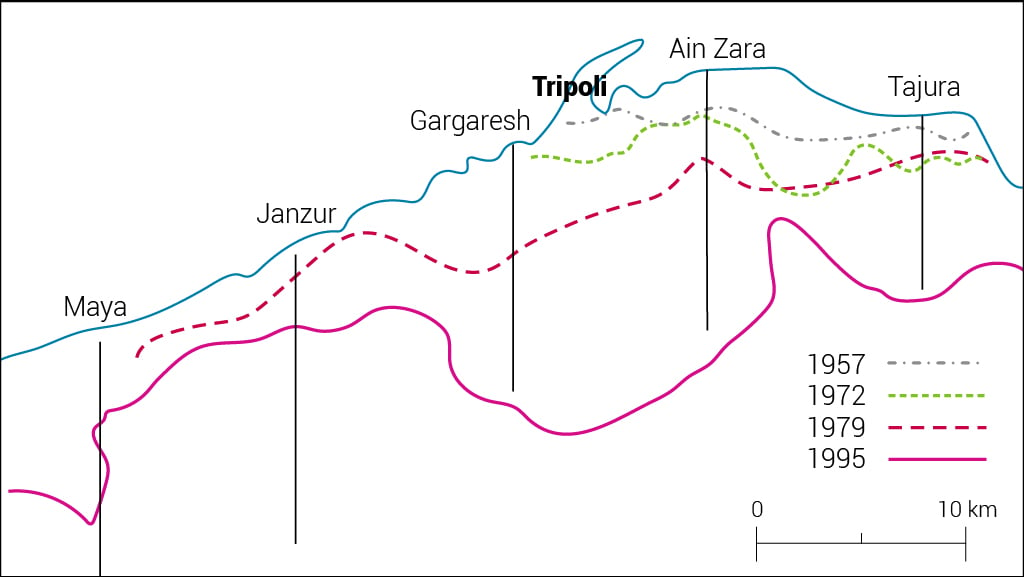

Contamination of the environment is encountered from different sources, namely seawater intrusion into the coastal aquifer, brine discharge from desalination plants, unlined municipal landfill sites, direct discharge of sewage into wadis and the uncontrolled dumping of industrial waste.[16]However, seawater intrusion as a result of excessive groundwater abstraction is considered the most serious groundwater pollutant. Map 1 show the saltwater-freshwater transition zone advanced inland by between 5-10 kilometres in the Tripoli area in the period 1957-1995 as a result of the high draw down of the groundwater level, accompanied by increasing salinity up to 18,000 mg/L in 1995.[17] [18]

Desalination plants, whether they are public or private, reportedly discharge brine into the soil or directly into wells, the sewerage network or sea. The impact of WWTPs is little better, as they are allegedly discharging untreated waste water into wadis and depressions, with some plants discharging directly into the sea.[20]

High nitrate concentrations were recorded in shallow groundwater aquifers of agricultural projects in the south of Libya as well as in the aquifers in extremely populated areas.[21] However, contamination as a result of exhaustive agricultural activities is still rare.

[1] CEDARE, 2014.Libya Water Sector M&E Rapid Assessment Report. Monitoring and Evaluation for Water in North Africa (MEWINA) project, Water Resources Management Program, CEDARE.

[2] Pallas P, 1980. Water resources of the Great Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriya. The Geology of Libya, Second Symposium, Volume 2.

[3] Ibid.

[4] ARC-ICARDA, 2008. Partnership Between the Libyan Agricultural Research Center (ARC) and the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA).

[5] Pallas P, 1980. Water resources of the Great Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriya. The Geology of Libya, Second Symposium, Volume 2.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] ARC-ICARDA, 2008. Partnership Between the Libyan Agricultural Research Center (ARC) and the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA).

[9] Pallas P, 1980. Water resources of the Great Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriya. The Geology of Libya, Second Symposium, Volume 2.

[10] ARC-ICARDA, 2008. Partnership Between the Libyan Agricultural Research Center (ARC) and the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA).

[11] El-Kabir A, 2019.Study of curing sulphuric water in the central part of Libya and its prospective future using GIS system. Libyan Authority of Natural Science Research and Technology unpublished report.

[12] CEDARE, 2014.Libya Water Sector M&E Rapid Assessment Report. Monitoring and Evaluation for Water in North Africa (MEWINA) project, Water Resources Management Program, CEDARE.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] General Water Authority , 2014 , Water and Energy for Life in Libya (WELL) , Project funded by the European Commission No. 295143, FP7, Libya.

[17] Sadeg, Saleh, 1996. Numerical Simulation of Saltwater Intrusion in Tripoli, Libya. PhD thesis, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey.

[18] University Engineering Consulting Office, 2002.Study of the Seawater Intrusion in North West Libya. General Water Authority, unpublished report, volume II.

[19] CEDARE, 2014.Libya Water Sector M&E Rapid Assessment Report. Monitoring and Evaluation for Water in North Africa (MEWINA) project, Water Resources Management Program, CEDARE.

[20] General Water Authority , 2014 , Water and Energy for Life in Libya (WELL) , Project funded by the European Commission No. 295143, FP7, Libya.

[21] Ibid.