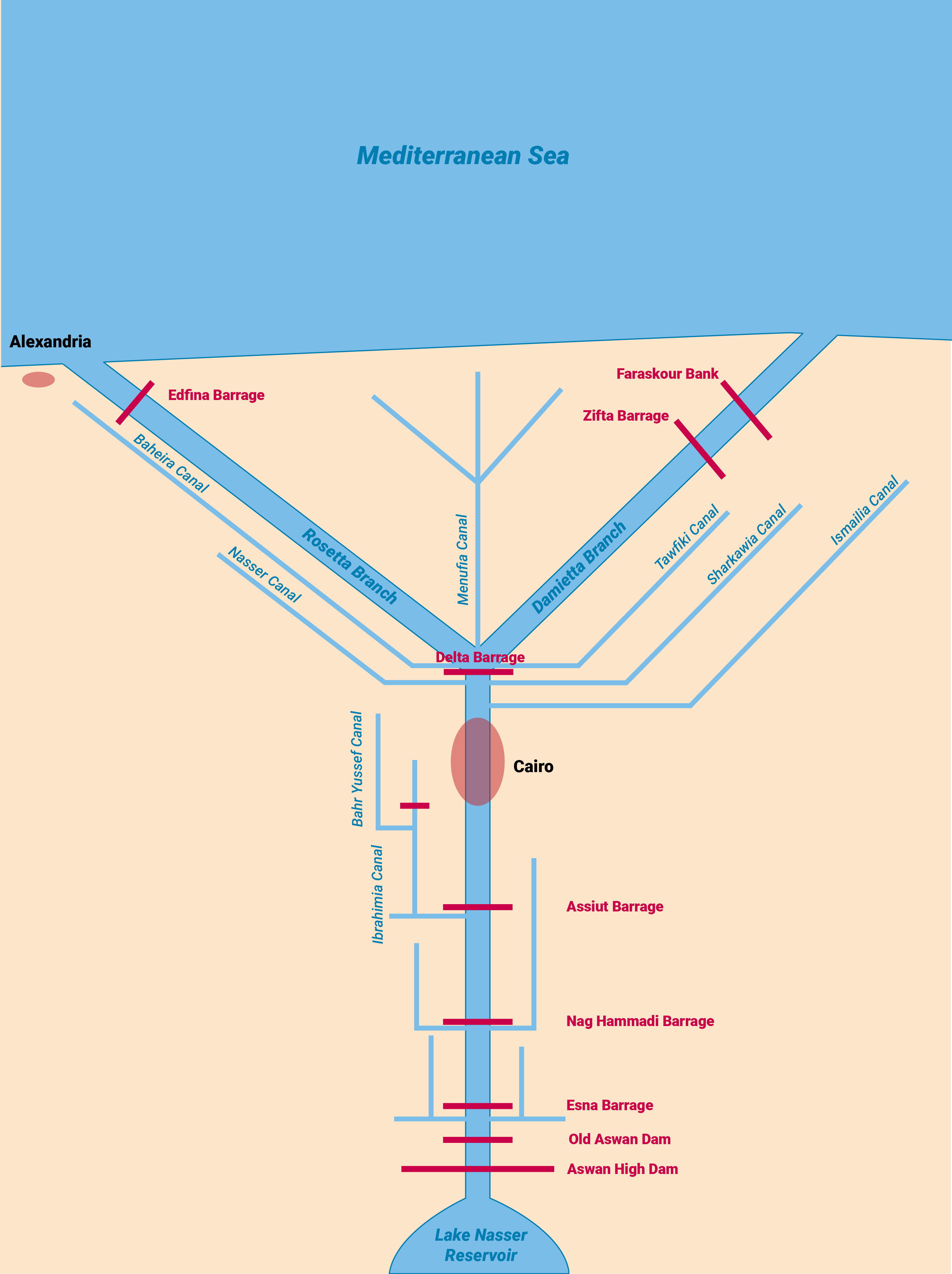

The main water infrastructure in Egypt is on the River Nile, notably the Aswan High Dam, the Aswan Old Dam and several downstream barrages.

Dams and barrages

In order to boost the level of water upstream to supply the irrigation canals and regulate navigation, a series of diversion dams (barrages or weirs) were built across the Nile at the head of the delta about 20 km downstream from Cairo. The Nile Valley’s modern irrigation system may have started with this Delta Barrage construction, which was not finished until 1861 but was later enlarged and upgraded. Almost halfway down the Damietta branch of the deltaic Nile, the Zifta Barrage was added to this system in 1901. Assiut Barrage, located more than 200 km upstream from Cairo, was constructed in 1902. Following this came the barrage at Esna, located about 257 km above Assiut, and the barrage at Nag Hammadi, about 240 km above Assiut, built in 1930.

In 1898, the Aswan Low Dam was constructed. The dam, which was established in 1902, was raised twice between 1907 and 1912, then twice more between 1929 and 1933 to further reduce flooding of the Nile. The dam was not enough to halt the yearly floods, however, and in 1952 the idea of building a higher dam with funding from the World Bank was born.

The northern border between Egypt and Sudan is marked by the rock-filled Aswan High Dam. The reservoir generates Lake Nasser, and the dam feeds the Nile. The project’s construction began in 1960 and was finished in 1968. In 1971, it was formally inaugurated. One billion dollars was invested in total for the dam’s construction. The Aswan High Dam’s 132 km3 reservoir can hold enough water to irrigate 33,600 km2 of land. It assists Egypt and Sudan with their agricultural demands, manages floods, produces electricity and facilitates better navigation on the Nile. Twelve power turbines are fuelled by water from the dam, which supplies half of Egypt’s energy needs. During droughts, the reservoir also aids in supplying water.

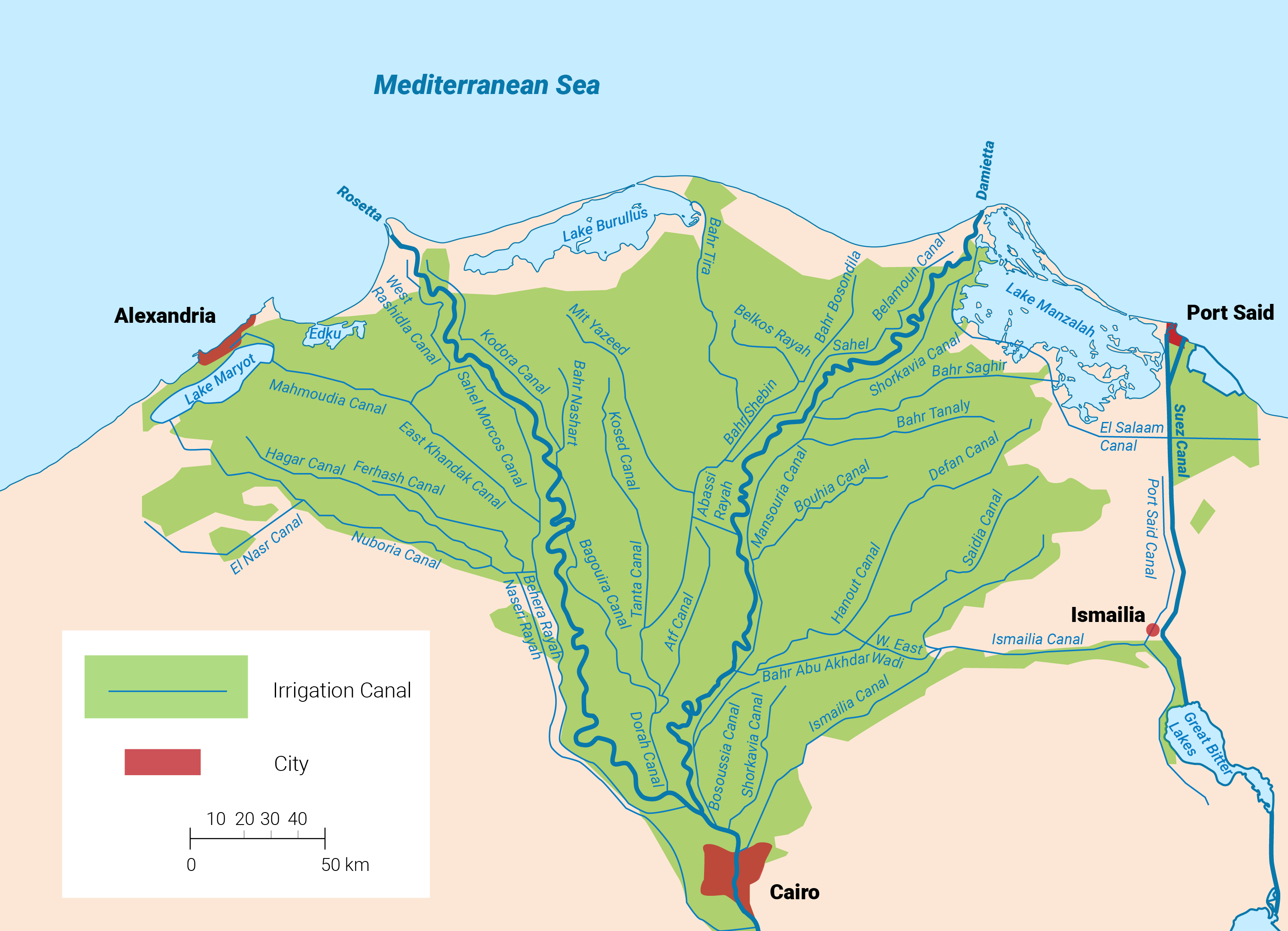

Irrigation system

A hierarchy of public canals, including carriers or primary canals, main canals, secondary (or branch) canals and tertiary (or sub-branch) canals, is used to divert water from the Nile to agricultural lands. The branch canals feed water into so-called mesqas, which are private canals. A sophisticated rotational system governs the distribution of water and supply to the farm level. The Nile Delta, in particular, has a vast canal system. The administration and upkeep of the public system fall under the purview of the government. Each mesqa served by this system has a service area of 20-80 hectares. Farm ditches called merwas, which can supply up to 8 hectares, are fed by mesqas.[4]

The Egyptian government launched a two-year project to line canals and irrigation channels by covering the earthen surface with concrete walls that prevent water leakage. The project aims to reduce water loss through infiltration into the subsurface area by 30-40%. The cost of the final scheme for the rehabilitation and development of the main canals at the national level is 2.6 billion US dollars. The scheme, announced in 2020, calls for the lining and maintenance of 20,000 km of canals.[5]

Hydropower

There are six hydroelectric power stations in Egypt with a total design capacity of 3,144 megawatts (MW). However, the actual production ranged between 2,800 and 2,832 MW in the period from 2012 to 2021, which is 3% of Egypt’s energy production.

Table 1. Hydropower stations in Egypt.

| Hydropower station | Capacity (MW) |

| Aswan High Dam | 2,400 |

| Aswan reservoirs (1 and 2) | 550 |

| Esna | 84.4 |

| Nag Hammadi | 66.2 |

| Assiut | 43.5 |

Wastewater treatment infrastructure

With more than 75% of Egypt’s rural areas still lacking access to wastewater treatment facilities, the World Bank estimates that $14 billion in investments are required to bring the coverage of the sewage system up to 100%. Egypt relies heavily on biological wastewater treatment as the main technique to remove chemical and biological contaminants. There are 146 wastewater treatment plants with a total daily capacity of 5 MCM. The following biological treatments are the most popular in Egypt:

• Biological filters

• Rotary biological contactors

• Activated sludge

• Oxidation ponds

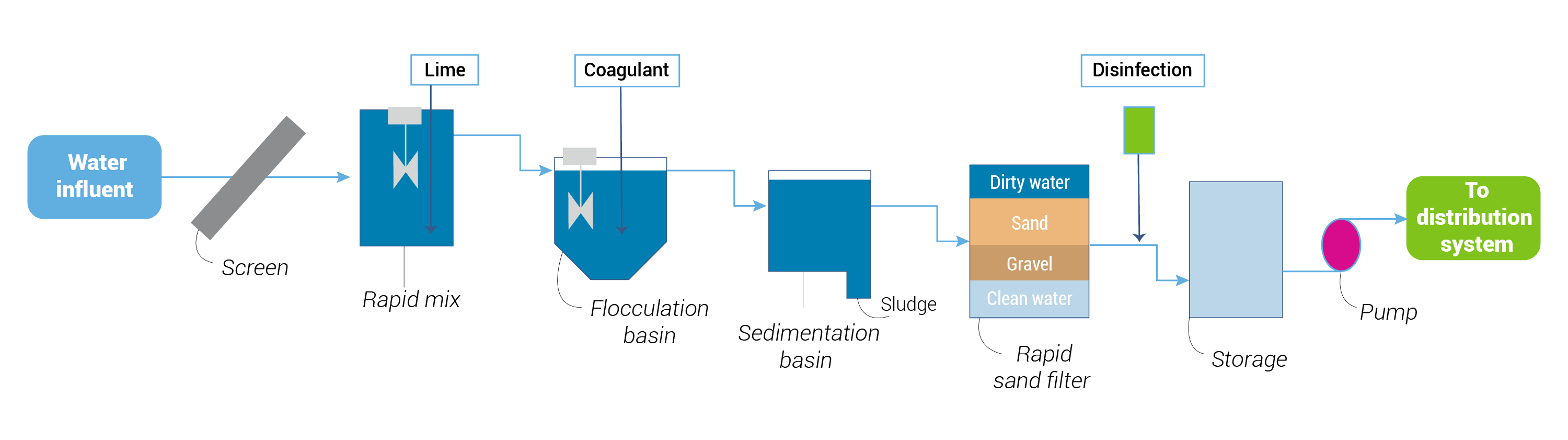

The Bahr al-Baqar wastewater treatment plant in north-west Egypt is the biggest in Africa and among the biggest in the world. As a result of irrigation with untreated municipal, industrial and agricultural wastewater, there was previously a risk of contamination. By recycling the water from the Bahr al-Baqar drain, the wastewater treatment plant, which generates 2.04 BCM annually, provides a sustainable solution for environmental pollution recovery and produces irrigation water to support the cultivation of 168,000 hectares adjacent to the Suez Canal. The total footprint of the Bahr al-Baqar treatment facility is 650,000 m2. The facility has cutting-edge systems for pumping raw water, coagulation, flocculation, decantation, filtration and disinfection to create water of a high quality for irrigating nearby crops.

Drinking water treatment infrastructure

Egypt primarily relies on conventional surface water treatment (sand filtration followed by chlorine disinfection; 91.46%) to supply drinking water to its citizens, with groundwater and desalination accounting for 8.3% and 0.2%, respectively.[3] To provide high-quality drinking water at a low cost, the government has expanded the use of natural-based treatment techniques such as riverbank filtration. There are now more than 160 riverbank filtration projects for domestic water use, but they still represent less than 1% of the total drinking water production.[2]

[1] Abu Shmeis, R.M., 2018, Chapter One – Water chemistry and microbiology, in Comprehensive Analytical Chemistry, D.S. Chormey, et al., Editors. Elsevier. 1-56.

[2] Mahmoud, A.R.A., 2021.Effectiveness of bank filtration for water supply in arid climates: A case study in Egypt. CRC Press.

[3] Ghodeif, K., Grischek, T., et al., 2016.Potential of river bank filtration (RBF) in Egypt. Environmental Earth Sciences, 75(8): 671.

[4] Barnes, J., 2016.States of maintenance: Power, politics, and Egypt’s irrigation infrastructure. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 35(1): 146-164.

[5] Abd-Elaty, I., Pugliese, L., et al., 2022.Modelling the impact of lining and covering irrigation canals on underlying groundwater stores in the Nile Delta, Egypt. Hydrological Processes, 36(1): e14466.